Following the recent Wireless Waffle post about Wes's excellent Soldery Song, it has been noted that the terms 'C-Band' and 'Ku-Band' were thrown around casually, as if everyone understands what these mean. For the benefit of those who don't, here's a short description of what they're all about:

It is perhaps no surprise that in the battle to gain access to Ka-Band, some of those doing the fighting are going to lose out. This seems to have happened to Australian satellite company NewSat. Recently both Morgan Stanley and Lazard have pulled out of the programme raising funds for the launch of NewSat's Jabiru 1 satellite. Digging into the economics of NewSat, it appears that the numbers just don't add up. The cost of their capacity would be around 50% higher than that of existing Ka-Band satellite operators, which might be a difficult sell when trying to raise lots of capital to build and launch a new satellite.

It is perhaps no surprise that in the battle to gain access to Ka-Band, some of those doing the fighting are going to lose out. This seems to have happened to Australian satellite company NewSat. Recently both Morgan Stanley and Lazard have pulled out of the programme raising funds for the launch of NewSat's Jabiru 1 satellite. Digging into the economics of NewSat, it appears that the numbers just don't add up. The cost of their capacity would be around 50% higher than that of existing Ka-Band satellite operators, which might be a difficult sell when trying to raise lots of capital to build and launch a new satellite.

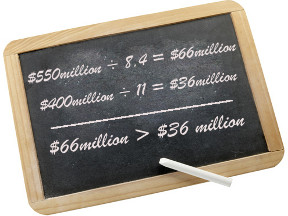

From the figures on their web-site, NewSat were going to pay Lockheed Martin US$550 million to build and launch their 'bird'. The resulting satellite would operate in a total of around 8.4 GHz of Ka-Band spectrum. Compare that to UK satellite company Avanti who paid US$400 million for their bird, but which accesses 11 GHz worth of Ka-Band spectrum. Do the maths and you see that NewSat would be paying approximately US$66 million to access each GHz of spectrum, whereas Avanti paid only US$36 million. This difference in cost is borne out in prices too, with NewSat claiming to be aiming to charge customers US$1.3 million for a transponder for 12 months. The equivalent price for Avanti is around US$0.9 million.

From the figures on their web-site, NewSat were going to pay Lockheed Martin US$550 million to build and launch their 'bird'. The resulting satellite would operate in a total of around 8.4 GHz of Ka-Band spectrum. Compare that to UK satellite company Avanti who paid US$400 million for their bird, but which accesses 11 GHz worth of Ka-Band spectrum. Do the maths and you see that NewSat would be paying approximately US$66 million to access each GHz of spectrum, whereas Avanti paid only US$36 million. This difference in cost is borne out in prices too, with NewSat claiming to be aiming to charge customers US$1.3 million for a transponder for 12 months. The equivalent price for Avanti is around US$0.9 million.

This may not yet be a Ka-tastrophe (groan) or even a Ka-lamity (double groan) for NewSat. NewSat suspended trading in its shares in November to give it time to re-think it's financing strategy. Maybe there is still a 'hope in heaven' for those communities that NewSat was intending to serve, if, of course, the other satellite operators don't get there first!

- C-Band (in satellite terms) refers to frequencies in the range of roughly 4 to 8 GHz. C-Band satellites are commonplace in areas where there is very heavy rainfall (eg tropical areas) as, using relatively low microwave frequencies, signals propagate better and suffer fewer rain fades. It's not the total amount of rain that matters, it's the voracity of the downpours.

- Ku-Band refers to frequencies roughly in the range of 10 to 15 GHz (the 'roughly' refering to the fact that uplinks and downlinks work in different bands that may or may not be within this range but are at least somewhere nearby). Ku-Band is the band most commonly used for digital satellite television broadcasting anywhere that it doesn't rain too heavily (eg most non-tropical areas). In many areas, the geostationary arc is near saturation in Ku-Band, with satellites positioned every 2 degrees or so. Some satellite operators have tried to launch broadband internet services in this band but the high levels of congestion make it difficult to find the space to do so.

- Ka-Band refers to frequencies roughly in the range of 20 to 30 GHz. Ka-Band is the relative newcomer on the block (though Italsat F1 conducted some tests in this band in the early 1990s). With Ku-Band becoming congested with broadcasting, satellite operators wishing to offer broadband services are increasingly turning to Ka-Band to do so and it is fast becoming the most hotly contested band for new satellite services. Already popular in the US, it is now being successfully commercialised in Europe and Africa. In emerging countries, where terrestrial (including wireless) broadband services are unlikely to be rolled-out any time soon, the use of Ka-Band satellite broadband is likely to open up Internet access to millions of people who wouldn't otherwise have a hope of getting a decent connection.

It is perhaps no surprise that in the battle to gain access to Ka-Band, some of those doing the fighting are going to lose out. This seems to have happened to Australian satellite company NewSat. Recently both Morgan Stanley and Lazard have pulled out of the programme raising funds for the launch of NewSat's Jabiru 1 satellite. Digging into the economics of NewSat, it appears that the numbers just don't add up. The cost of their capacity would be around 50% higher than that of existing Ka-Band satellite operators, which might be a difficult sell when trying to raise lots of capital to build and launch a new satellite.

It is perhaps no surprise that in the battle to gain access to Ka-Band, some of those doing the fighting are going to lose out. This seems to have happened to Australian satellite company NewSat. Recently both Morgan Stanley and Lazard have pulled out of the programme raising funds for the launch of NewSat's Jabiru 1 satellite. Digging into the economics of NewSat, it appears that the numbers just don't add up. The cost of their capacity would be around 50% higher than that of existing Ka-Band satellite operators, which might be a difficult sell when trying to raise lots of capital to build and launch a new satellite. From the figures on their web-site, NewSat were going to pay Lockheed Martin US$550 million to build and launch their 'bird'. The resulting satellite would operate in a total of around 8.4 GHz of Ka-Band spectrum. Compare that to UK satellite company Avanti who paid US$400 million for their bird, but which accesses 11 GHz worth of Ka-Band spectrum. Do the maths and you see that NewSat would be paying approximately US$66 million to access each GHz of spectrum, whereas Avanti paid only US$36 million. This difference in cost is borne out in prices too, with NewSat claiming to be aiming to charge customers US$1.3 million for a transponder for 12 months. The equivalent price for Avanti is around US$0.9 million.

From the figures on their web-site, NewSat were going to pay Lockheed Martin US$550 million to build and launch their 'bird'. The resulting satellite would operate in a total of around 8.4 GHz of Ka-Band spectrum. Compare that to UK satellite company Avanti who paid US$400 million for their bird, but which accesses 11 GHz worth of Ka-Band spectrum. Do the maths and you see that NewSat would be paying approximately US$66 million to access each GHz of spectrum, whereas Avanti paid only US$36 million. This difference in cost is borne out in prices too, with NewSat claiming to be aiming to charge customers US$1.3 million for a transponder for 12 months. The equivalent price for Avanti is around US$0.9 million.This may not yet be a Ka-tastrophe (groan) or even a Ka-lamity (double groan) for NewSat. NewSat suspended trading in its shares in November to give it time to re-think it's financing strategy. Maybe there is still a 'hope in heaven' for those communities that NewSat was intending to serve, if, of course, the other satellite operators don't get there first!

7 comments

( 2859 views )

| permalink

|

( 2.9 / 1599 )

( 2.9 / 1599 )

( 2.9 / 1599 )

( 2.9 / 1599 )

Wireless Waffle received an e-mail from Des of Ireland. Des writes:

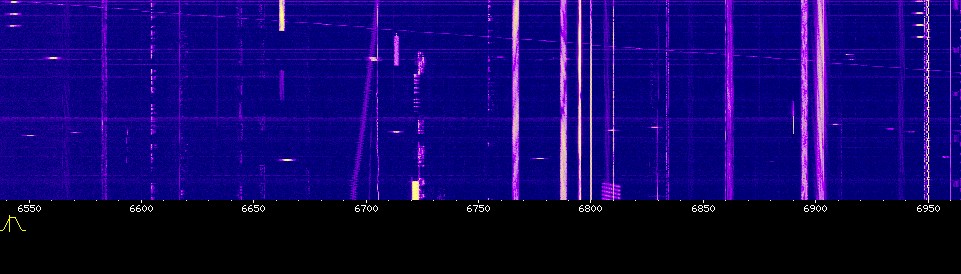

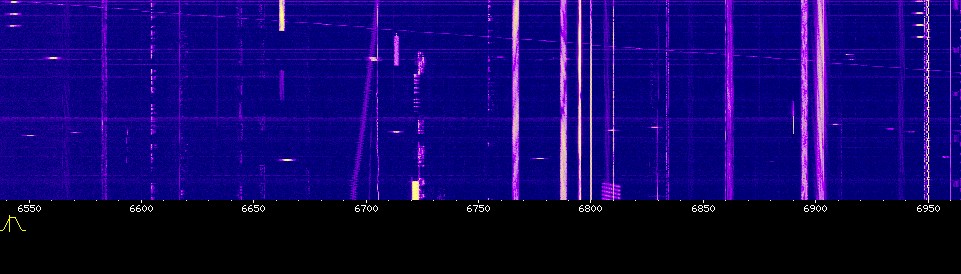

Take a look a the picture below (click on it to open a much larger version). It is a snapshot of the radio spectrum between roughly 6550 and 6950 kHz taken using the University of Twente's on-line receiver in the Netherlands (which is a marvel in itself). The snapshot was taken at about 07:00 GMT. The horizontal axis shows the frequency, the vertical axis is time (in thie case about a minute). Straight vertical lines represent constant transmissions. Dotted ones (such as the broken line just above 6600 kHz) are morse code. Other squiggles that are roughly vertical are all manner of other signals that can be found on the HF bands.

What is of interest here are the horizontal dashes of which there are three at the top left hand corner (just under 6550 kHz), four just below 6950 kHz and various others scattered across the chart, seemingly randomly (see around 6665 kHz and 6555 kHz for two bright ones). These are not bugs in the University's software, nor are they local interference in Twente. What they are are bursts of data from a frequency hopping transmitter. If you tune into one of the frequencies just at the time when the transmission is taking place on that frequency, you will hear a 'chuff' noise which is the quick burst of data that is being sent. If you happen across a frequency that has multiple 'hops' on it, the effect is not totally unlike there being a steam train on the frequency (listen to this actual recording).

At HF, this hopping transmission is almost certainly military in nature. Frequency hopping at HF is not at all uncommon. Even back in the 1980s, Racal's TRA 931XH would happily hop around the HF bands. In the case of the '931XH it did this by changing frequency roughly every second. Transmissions were just SSB (with an initial data burst to synchronise the receiver and transmitter - this is essential so that the two follow the same sequence of frequencies). The Wireless Waffle team had the fun of seeing a demo of the '931XH which was set to hop from frequencies between around 6950 and 7450 kHz, right across the 41m broadcast band. The effect of the hopping was to change the background noise every second or so - sometimes with a loud whistle caused by the carriers of the broadcast signals. The effect to anyone who happened to listen on a frequency that was being used would have been that they would have heard speech for a second which would then disappear.

There's nothing unusual about the use of frequency hopping transmitters. Your bluetooth headset does this, and most GSM networks are set up to use frequency hopping too. The reason for using frequency hopping can be many and various, such as:

There's nothing unusual about the use of frequency hopping transmitters. Your bluetooth headset does this, and most GSM networks are set up to use frequency hopping too. The reason for using frequency hopping can be many and various, such as:

Since early May I have been noticing many many frequencies being occupied by very short bursts of digital 'noise' which are random in their frequency and time but very recognisable. So far pattern emerged is that they follow an 8 kHz spacing right across the HF bands (from 3.4 MHz to 28.5 MHz), but mainly in 6 to 9 MHz region. Even 6622kHz Shanwick being clobbered ... These noise bursts in the HF bands intrigue me, I wondered if it is a basic military comms set-up in case satellites/internet/microwave/fible-cable are clobbered.

Take a look a the picture below (click on it to open a much larger version). It is a snapshot of the radio spectrum between roughly 6550 and 6950 kHz taken using the University of Twente's on-line receiver in the Netherlands (which is a marvel in itself). The snapshot was taken at about 07:00 GMT. The horizontal axis shows the frequency, the vertical axis is time (in thie case about a minute). Straight vertical lines represent constant transmissions. Dotted ones (such as the broken line just above 6600 kHz) are morse code. Other squiggles that are roughly vertical are all manner of other signals that can be found on the HF bands.

What is of interest here are the horizontal dashes of which there are three at the top left hand corner (just under 6550 kHz), four just below 6950 kHz and various others scattered across the chart, seemingly randomly (see around 6665 kHz and 6555 kHz for two bright ones). These are not bugs in the University's software, nor are they local interference in Twente. What they are are bursts of data from a frequency hopping transmitter. If you tune into one of the frequencies just at the time when the transmission is taking place on that frequency, you will hear a 'chuff' noise which is the quick burst of data that is being sent. If you happen across a frequency that has multiple 'hops' on it, the effect is not totally unlike there being a steam train on the frequency (listen to this actual recording).

At HF, this hopping transmission is almost certainly military in nature. Frequency hopping at HF is not at all uncommon. Even back in the 1980s, Racal's TRA 931XH would happily hop around the HF bands. In the case of the '931XH it did this by changing frequency roughly every second. Transmissions were just SSB (with an initial data burst to synchronise the receiver and transmitter - this is essential so that the two follow the same sequence of frequencies). The Wireless Waffle team had the fun of seeing a demo of the '931XH which was set to hop from frequencies between around 6950 and 7450 kHz, right across the 41m broadcast band. The effect of the hopping was to change the background noise every second or so - sometimes with a loud whistle caused by the carriers of the broadcast signals. The effect to anyone who happened to listen on a frequency that was being used would have been that they would have heard speech for a second which would then disappear.

There's nothing unusual about the use of frequency hopping transmitters. Your bluetooth headset does this, and most GSM networks are set up to use frequency hopping too. The reason for using frequency hopping can be many and various, such as:

There's nothing unusual about the use of frequency hopping transmitters. Your bluetooth headset does this, and most GSM networks are set up to use frequency hopping too. The reason for using frequency hopping can be many and various, such as:- Hopping around makes the transmission much more difficult to detect. Unless you know the sequence of frequencies being used, it's almost impossible to follow the transmission from one frequency to the next.

- Hopping can overcome some kinds of interference. If one frequency is blocked (from a broadcast transmission for example) the information sent on that frequency is lost, but if most are clear of interference, the error correction schemes can be arranged to deal with missing blocks and the overall communication is unaffected.

- Hopping can help overcome fading and propagation problems. In a GSM network for example, Rayleigh fading will cause some channels to have deep fades and others not. Hopping around makes sure that these 'dead' channels do not cause a total lack of communication.

About 18 months ago, the Wireless Waffle team wrote a paper on the topic of what radio amateurs in the UK might have to pay if spectrum pricing was applied to the spectrum they use. The paper was offered to the RSGB and to Practical Wireless as material that could be used for an article in their prestigious magazines.

The RSGB indicated that it was not the sort of article they normally published as it didn't have antennas in it or any pictures of people standing on a mountain or remote desert island. Practical Wireless never responded as they were too busy assessing the merits of the latest amateur radio gizmo to come from Latin America (see right) and the whole thing got shoved to the bottom of the 'to do' pile and forgotten about. At least I think that was what the RSGB and PW said, the old memory is a bit hazy on the subject.

The RSGB indicated that it was not the sort of article they normally published as it didn't have antennas in it or any pictures of people standing on a mountain or remote desert island. Practical Wireless never responded as they were too busy assessing the merits of the latest amateur radio gizmo to come from Latin America (see right) and the whole thing got shoved to the bottom of the 'to do' pile and forgotten about. At least I think that was what the RSGB and PW said, the old memory is a bit hazy on the subject.

Whilst the material contained in the paper is now around a year old, it still makes for interesting reading and it is almost certain that Wireless Waffle readers will find it worth the time to study. Rather than think what to do with it next, it has been uploaded to the web-site and is now available for anyone to download and read.

So, for your reading pleasure, we present 'The Duffer's Guide to Spectrum Pricing. Pour yourself a beer, turn on your VHF radio, and have a read. Then, if you are a radio ham, realise how lucky you are to be able to afford that beer you just poured yourself!

The RSGB indicated that it was not the sort of article they normally published as it didn't have antennas in it or any pictures of people standing on a mountain or remote desert island. Practical Wireless never responded as they were too busy assessing the merits of the latest amateur radio gizmo to come from Latin America (see right) and the whole thing got shoved to the bottom of the 'to do' pile and forgotten about. At least I think that was what the RSGB and PW said, the old memory is a bit hazy on the subject.

The RSGB indicated that it was not the sort of article they normally published as it didn't have antennas in it or any pictures of people standing on a mountain or remote desert island. Practical Wireless never responded as they were too busy assessing the merits of the latest amateur radio gizmo to come from Latin America (see right) and the whole thing got shoved to the bottom of the 'to do' pile and forgotten about. At least I think that was what the RSGB and PW said, the old memory is a bit hazy on the subject.Whilst the material contained in the paper is now around a year old, it still makes for interesting reading and it is almost certain that Wireless Waffle readers will find it worth the time to study. Rather than think what to do with it next, it has been uploaded to the web-site and is now available for anyone to download and read.

So, for your reading pleasure, we present 'The Duffer's Guide to Spectrum Pricing. Pour yourself a beer, turn on your VHF radio, and have a read. Then, if you are a radio ham, realise how lucky you are to be able to afford that beer you just poured yourself!

Although the standard for WiFi at 5 GHz has been around for a long time, most manufacturers have focused upon producing equipment for the 2.4 GHz band. The reason for this is a simple one - it's cheaper! The higher you go in frequency, the more difficult, and therefore expensive, it becomes to transmit and receive radio signals. As a result, home routers, laptops, smart phones and other devices have almost exclusively been equipped to use the 2.4 GHz band for their WiFi connection.

Although the standard for WiFi at 5 GHz has been around for a long time, most manufacturers have focused upon producing equipment for the 2.4 GHz band. The reason for this is a simple one - it's cheaper! The higher you go in frequency, the more difficult, and therefore expensive, it becomes to transmit and receive radio signals. As a result, home routers, laptops, smart phones and other devices have almost exclusively been equipped to use the 2.4 GHz band for their WiFi connection.Previous Wireless Waffle articles have discussed how to select the best WiFi channels in the 2.4 GHz band, and other techniques, to maximise coverage and signal quality, however we have not looked at the 5 GHz band. Recently, there seem to be a slew of articles which are claiming that using 5 GHz will produce better range and more reliable connections compared to 2.4 GHz. The logic of these articles seems to go '5 is a bigger number than 2.4 - in fact it is more than double - so it must be at least twice as good'. This, sad to say, is not the case. Here are the real facts:

- Signals at 5 GHz only travel HALF as far as those on 2.4 GHz as higher frequencies have poorer coverage than lower ones.

- Signals at 5 GHz will struggle almost TWICE AS HARD to get through walls than signals at 2.4 GHz due to their poorer propagation characteristics.

- 5 GHz WiFi equipment is subject to exactly the same POWER RESTRICTIONS as that for 2.4 GHz, so there is no inherent advantage in terms of the technology itself.

- The use of some of the 5 GHz channels is subject to the requirement to STOP TRANSMITTING if a nearby radar is detected. No such restriction applies at 2.4 GHz.

- 5 GHz equipment will be (slightly) more POWER HUNGRY than its 2.4 GHz counterparts, increasing battery drain especially in mobile devices.

- 5 GHz receivers are likely to be LESS SENSITIVE than 2.4 GHz receivers because of the increased difficulty of making low noise devices at higher frequencies.

- The 5 GHz band consists of up to 25 (territory dependent) independent channels which can be used without interfering with each other meaning there is much GREATER CAPACITY for more networks, whereas the 2.4 GHz band has 13 channels of which only 3 can be used independently.

- The 2.4 GHz band is also used for Bluetooth, microwave ovens, wireless cameras and many other applications meaning it can be subject to a lot of background interference. The 5 GHz band is MUCH CLEANER, though the band is not exclusive to WiFi systems.

- There are still fewer 5 GHz devices around than 2.4 GHz once and hence it is likely to be LESS SUSCEPTIBLE TO SNOOPING.

For a home network, in a small house or apartment, using 5 GHz may offer some advantages given the lower interference it will suffer from other devices, but in large family homes a 5 GHz WiFi router is unlikely to be able to outperform the coverage and range that a 2.4 GHz router achieves.

Where the 5 GHz band may come into its own is when the not-quite-yet-finalised IEEE 802.11ac standard is adopted. This works in the 5 GHz bands and uses the greater capacity of the band to deliver connection speeds of up to 1 Gbps. For streaming media around, this has clear advantages. As a wireless distribution for a home internet connection, however, there is unlikely to be any improvement noticeable using 802.11ac than with the existing 802.11n standard which can already offer connections of over 100 Mbps - much faster than most home internet connections!

Where the 5 GHz band may come into its own is when the not-quite-yet-finalised IEEE 802.11ac standard is adopted. This works in the 5 GHz bands and uses the greater capacity of the band to deliver connection speeds of up to 1 Gbps. For streaming media around, this has clear advantages. As a wireless distribution for a home internet connection, however, there is unlikely to be any improvement noticeable using 802.11ac than with the existing 802.11n standard which can already offer connections of over 100 Mbps - much faster than most home internet connections!