A lot of countries are beginning to consider the use of what is known as 'C-band' for new 5G services. The C-band runs from 3400 - 4200 MHz and is a set of radio frequencies extensively used for satellite connections (and for some point-to-point fixed links and the odd point-to-multipoint network). The satellite uses connections fall into a number of categories:

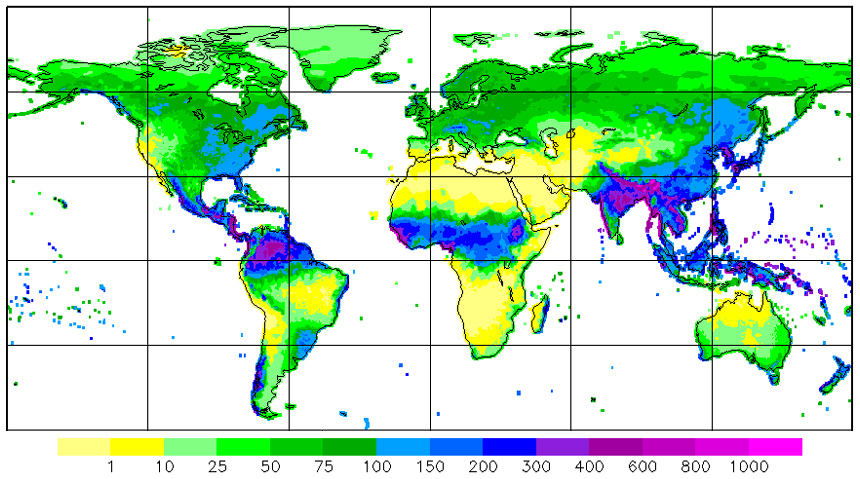

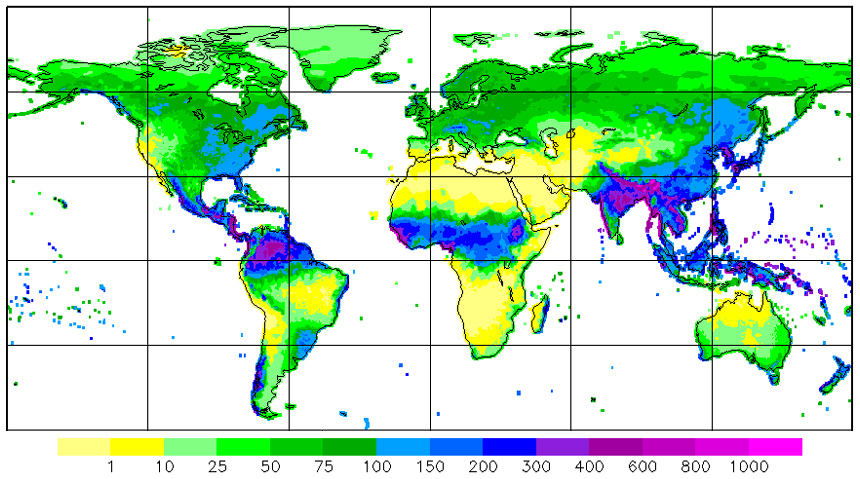

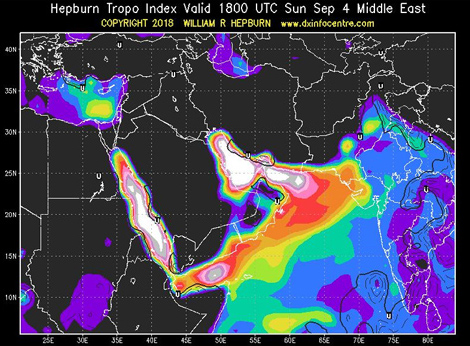

As can be seen from the map above (click for a bigger version), there is a swathe of the world, primarily in equatorial areas, where it really rains (those in blue and purple). In these areas, signals in other satellite frequency bands, such as Ku-band (11 GHz) and Ka-band (20 GHz) are absorbed so much by rain that when it pours, they become unreceivable but C-band being a lower frequency (4 GHz) does not. Using the band for 5G in countries where C-band is only lightly used is not impossible. Though 5G transmissions can wipe-out satellite reception in areas hundreds of kilometers from the 5G base stations, very careful planning of frequencies and site placements can lead to some solutions.

In countries, however, where there are hundreds of VSAT terminals, or thousands of domestic satellite receivers, the situation is more bleak. There is fundamentally no way that 5G networks and satellite receivers can share the same frequencies. The transmitter power of a satellite is not completely dissimilar to that of a 5G base station, but one is 40,000 kilometers away and the other may be 40 metres away. Clearly one will enormously overshadow the other.

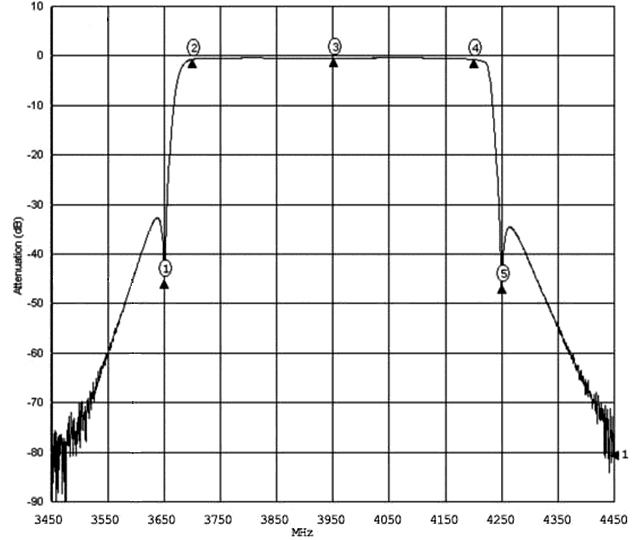

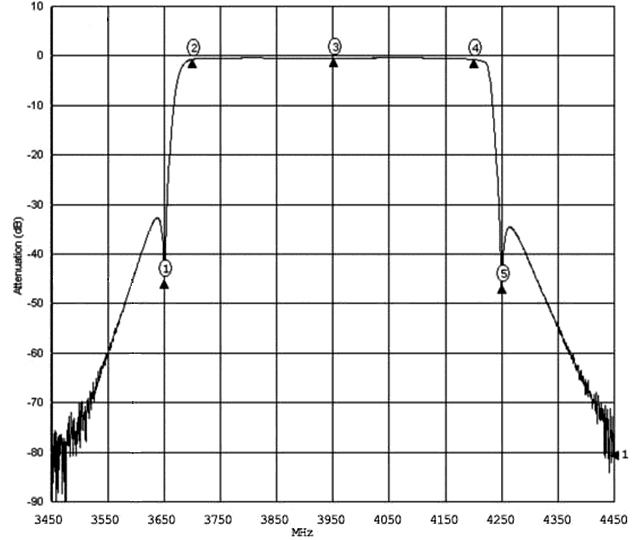

The only way that the two services can therefore co-exist is to separate the 5G frequencies from those used for satellite reception. As there are no 'unused' satellite frequencies in the C-band, this means that regulators have to take a decision to slice up the band, taking spectrum away from satellites and giving it to 5G services and this is what many have done. Hong Kong, Cambodia, Singapore and the Philippines (to mention a few) have decided to use frequencies from 3400 - 3600 MHz for 5G services, and leave 3700 - 4200 MHz for satellite services. The gap in-between (3600 - 3700 MHz) is left as a guard-band, a kind of no-mans-land in which neither service has priority. This allows satellite receivers to be fitted with filters which allow signals above 3700 MHz through, whilst rejecting signals below 3600 MHz (see the example on the right).

As there are no 'unused' satellite frequencies in the C-band, this means that regulators have to take a decision to slice up the band, taking spectrum away from satellites and giving it to 5G services and this is what many have done. Hong Kong, Cambodia, Singapore and the Philippines (to mention a few) have decided to use frequencies from 3400 - 3600 MHz for 5G services, and leave 3700 - 4200 MHz for satellite services. The gap in-between (3600 - 3700 MHz) is left as a guard-band, a kind of no-mans-land in which neither service has priority. This allows satellite receivers to be fitted with filters which allow signals above 3700 MHz through, whilst rejecting signals below 3600 MHz (see the example on the right).

In such a scenario, there is still potential for interference to the satellite services in two possible ways:

The solution to this, would be to fit filters to the 5G transmitters to reduce the unwanted emissions, but this costs the mobile operators and they are not keen to do so. In some cases they are not even able to do so. The use of 'massive MIMO' antennas means that the transmitters and antennas are incorporated into a single unit, inside which there is no room to fit a filter.

The solution to this, would be to fit filters to the 5G transmitters to reduce the unwanted emissions, but this costs the mobile operators and they are not keen to do so. In some cases they are not even able to do so. The use of 'massive MIMO' antennas means that the transmitters and antennas are incorporated into a single unit, inside which there is no room to fit a filter.

Sharing of the C-band between satellite services and 5G networks therefore remains a thorny issue and it will be interesting to see how the problem is resolved. One option is, of course, to use a different band in areas where C-band satellite is in strong demand. The 2.6 GHz band (2500 - 2690 MHz) is currently built in to every 5G phone that is on the market and in the near future the millimetre wave bands (26 GHz and above) will form part of the ecosystem, so maybe the satellite operators will be left alone in their C-band spectrum in places where it never rains, but it pours.

- Lifeblood links for remote areas (including some countries whose only international connection is via satellite such as Ascension Island).

- VSAT connections for businesses (i.e. banks and petrol stations) and for remote internet connections.

- Domestic television reception.

As can be seen from the map above (click for a bigger version), there is a swathe of the world, primarily in equatorial areas, where it really rains (those in blue and purple). In these areas, signals in other satellite frequency bands, such as Ku-band (11 GHz) and Ka-band (20 GHz) are absorbed so much by rain that when it pours, they become unreceivable but C-band being a lower frequency (4 GHz) does not. Using the band for 5G in countries where C-band is only lightly used is not impossible. Though 5G transmissions can wipe-out satellite reception in areas hundreds of kilometers from the 5G base stations, very careful planning of frequencies and site placements can lead to some solutions.

In countries, however, where there are hundreds of VSAT terminals, or thousands of domestic satellite receivers, the situation is more bleak. There is fundamentally no way that 5G networks and satellite receivers can share the same frequencies. The transmitter power of a satellite is not completely dissimilar to that of a 5G base station, but one is 40,000 kilometers away and the other may be 40 metres away. Clearly one will enormously overshadow the other.

The only way that the two services can therefore co-exist is to separate the 5G frequencies from those used for satellite reception.

As there are no 'unused' satellite frequencies in the C-band, this means that regulators have to take a decision to slice up the band, taking spectrum away from satellites and giving it to 5G services and this is what many have done. Hong Kong, Cambodia, Singapore and the Philippines (to mention a few) have decided to use frequencies from 3400 - 3600 MHz for 5G services, and leave 3700 - 4200 MHz for satellite services. The gap in-between (3600 - 3700 MHz) is left as a guard-band, a kind of no-mans-land in which neither service has priority. This allows satellite receivers to be fitted with filters which allow signals above 3700 MHz through, whilst rejecting signals below 3600 MHz (see the example on the right).

As there are no 'unused' satellite frequencies in the C-band, this means that regulators have to take a decision to slice up the band, taking spectrum away from satellites and giving it to 5G services and this is what many have done. Hong Kong, Cambodia, Singapore and the Philippines (to mention a few) have decided to use frequencies from 3400 - 3600 MHz for 5G services, and leave 3700 - 4200 MHz for satellite services. The gap in-between (3600 - 3700 MHz) is left as a guard-band, a kind of no-mans-land in which neither service has priority. This allows satellite receivers to be fitted with filters which allow signals above 3700 MHz through, whilst rejecting signals below 3600 MHz (see the example on the right).In such a scenario, there is still potential for interference to the satellite services in two possible ways:

- strong signals from the 5G transmitters can overload the satellite receivers (even after the rejection provided by the filter); or

- unwanted emissions from the 5G transmitters on the frequencies being received by the satellites can cause interference.

The solution to this, would be to fit filters to the 5G transmitters to reduce the unwanted emissions, but this costs the mobile operators and they are not keen to do so. In some cases they are not even able to do so. The use of 'massive MIMO' antennas means that the transmitters and antennas are incorporated into a single unit, inside which there is no room to fit a filter.

The solution to this, would be to fit filters to the 5G transmitters to reduce the unwanted emissions, but this costs the mobile operators and they are not keen to do so. In some cases they are not even able to do so. The use of 'massive MIMO' antennas means that the transmitters and antennas are incorporated into a single unit, inside which there is no room to fit a filter.Sharing of the C-band between satellite services and 5G networks therefore remains a thorny issue and it will be interesting to see how the problem is resolved. One option is, of course, to use a different band in areas where C-band satellite is in strong demand. The 2.6 GHz band (2500 - 2690 MHz) is currently built in to every 5G phone that is on the market and in the near future the millimetre wave bands (26 GHz and above) will form part of the ecosystem, so maybe the satellite operators will be left alone in their C-band spectrum in places where it never rains, but it pours.

add comment

( 932 views )

| permalink

|

( 3 / 62724 )

( 3 / 62724 )

( 3 / 62724 )

( 3 / 62724 )

The use of the radio spectrum in Europe is determined by a range of different organisations. At the truly international level, the ITU dictates which services are allocated which parts of the spectrum in its Radio Regulations which are updated every 3 to 4 years as the result of the World Radiocommunications Conference (WRC) at which every country in the world's regulators sit down and agree on any changes. At the more regional level, CEPT propose and make decisions on the use of spectrum in Europe. In the case of both the ITU and CEPT, several working groups are established to consider different topics such as fixed links, mobile services and satellite services.

A recent meeting of CEPT/ECC Working Group PT-A which took place in June in Prague, Czechia, was considering the items that should go on the agenda of the 2023 WRC, as these need to be agreed at the 2019 WRC to be held later this year. At this meeting, the French spectrum regulator, the ANFR, updated a proposal concerning:

A recent meeting of CEPT/ECC Working Group PT-A which took place in June in Prague, Czechia, was considering the items that should go on the agenda of the 2023 WRC, as these need to be agreed at the 2019 WRC to be held later this year. At this meeting, the French spectrum regulator, the ANFR, updated a proposal concerning:

Non-safety aeronautical mobile services are likely to consist of things such as the remote control of (military) drones. As a result of this submission, the meeting has proposed an item that will be taken by CEPT member countries to the next WRC which states:

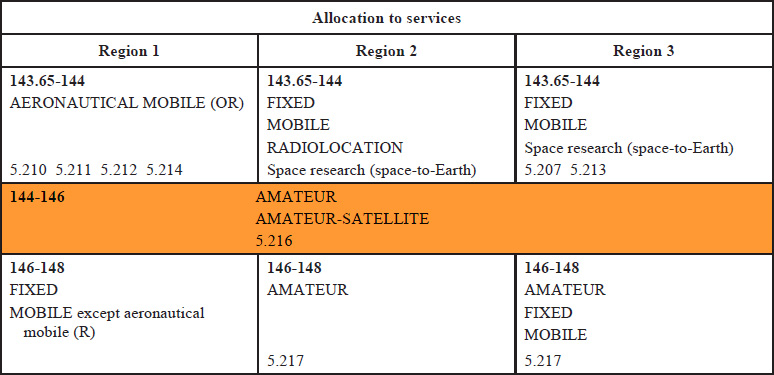

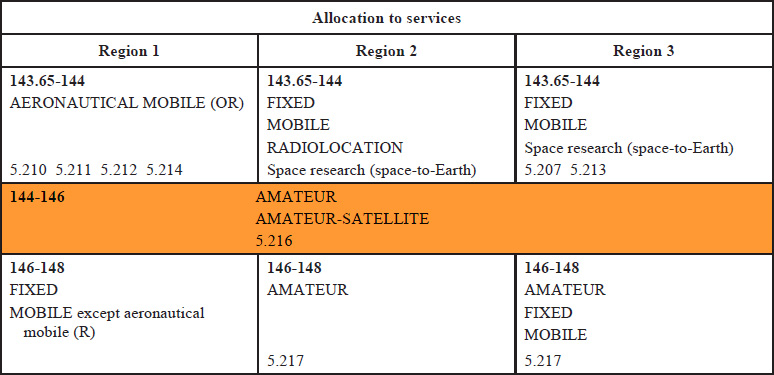

Hidden amongst this is a potential time-bomb for radio amateurs. The French administration is effectively proposing that the 2 metre amateur band (144 - 146 MHz) which is currently allocated for the exclusive use by radio amateurs, should be shared with non-safety aeronautical mobile services. Note that this is already the case in China and that in Region 1 (Europe) the spectrum immediately below the 144 MHz band is already allocate for Aeronautical Mobile services. The proposal does not state whether the new allocation should be on a secondary basis (in which case radio amateurs would continue to be protected from interference) or whether it would be on a co-primary basis (in which case both sets of users would have equivalent interference protection rights).

Hidden amongst this is a potential time-bomb for radio amateurs. The French administration is effectively proposing that the 2 metre amateur band (144 - 146 MHz) which is currently allocated for the exclusive use by radio amateurs, should be shared with non-safety aeronautical mobile services. Note that this is already the case in China and that in Region 1 (Europe) the spectrum immediately below the 144 MHz band is already allocate for Aeronautical Mobile services. The proposal does not state whether the new allocation should be on a secondary basis (in which case radio amateurs would continue to be protected from interference) or whether it would be on a co-primary basis (in which case both sets of users would have equivalent interference protection rights).

Wireless Waffle understands that the proposal was originated by French defence manufacturer Thales, and that their preferred outcome would be a co-primary allocation. Should this happen, notwithstanding the fact that there would be an interferer in the 2 metre band, the aeronautical services, if they suffered interference from amateurs, could them potential claim protection. It is not completely impossible that as a result of this, the amateur service could be either reduced to secondary status, or told to leave the band. Such an outcome would take at least 12 years, as it would first have to be put on the agenda for a future WRC (which could not be until at least 2027), then studied, before a decision could be made (at the eariest 2031).

Should radio amateurs be concerned. In a word, YES! The 2 metre band is very heavily used and is one of the only primary and exclusive amateur radio allocations that exists. A number of other amateur bands have recently been reduced or lost to other services (e.g. 2.3 GHz, 3.4 GHz) and there is also consideration of removing the amateur service from the 23cm band from 1260 to 1300 MHz to protect satellite navigation systems. However inconceivable it may be that the 2 metre band could go the same way, it is not impossible.

What can radio amateurs do? It is the national radio spectrum administrations who attends the CEPT/ECC meetings and represents the views of their country. In the first instance, therefore, amateurs should write to their national regulator (e.g. Ofcom in the UK) and express the importance of keeping the 2 metre band primary and exclusive for amateur use.

What can radio amateurs do? It is the national radio spectrum administrations who attends the CEPT/ECC meetings and represents the views of their country. In the first instance, therefore, amateurs should write to their national regulator (e.g. Ofcom in the UK) and express the importance of keeping the 2 metre band primary and exclusive for amateur use.

International organisations such as the IARU and national organisations such as the RSGB get involved to support the interests of radio amateurs, but this can only succeed if the national administrations listen empathetically.

If national administrations fail to support the amateur service, the next step would probably be for radio amateurs to protest outside CEPT/ECC meetings to try and demonstrate to CEPT just how strongly they object.

A recent meeting of CEPT/ECC Working Group PT-A which took place in June in Prague, Czechia, was considering the items that should go on the agenda of the 2023 WRC, as these need to be agreed at the 2019 WRC to be held later this year. At this meeting, the French spectrum regulator, the ANFR, updated a proposal concerning:

A recent meeting of CEPT/ECC Working Group PT-A which took place in June in Prague, Czechia, was considering the items that should go on the agenda of the 2023 WRC, as these need to be agreed at the 2019 WRC to be held later this year. At this meeting, the French spectrum regulator, the ANFR, updated a proposal concerning:an agenda item for new non-safety aeronautical mobile applications.

Non-safety aeronautical mobile services are likely to consist of things such as the remote control of (military) drones. As a result of this submission, the meeting has proposed an item that will be taken by CEPT member countries to the next WRC which states:

New non-safety aeronautical mobile applications will support applications like: imagery, video, fire and border surveillance, environment monitoring, traffic/disaster monitoring. Such applications require ground to air, air to ground and air to air, communications on-board manned and unmanned aircraft. Use of innovative sharing methods may be considered to ensure the protection of existing services while offering the possibility to have access to new frequency bands. Several frequency bands are proposed for investigation within different ranges in order to meet the various operational requirements for new non-safety aeronautical mobile applications.

It is proposed to study the bands 162.0375-174.000 MHz, 862-874 MHz and 22-22.21 GHz in order to evaluate the possible revision or deletion of the "except aeronautical mobile" restriction and the bands 144-146 MHz, 5000-5010 MHz and 15.4-15.7 GHz for possible new allocations to the aeronautical mobile service.

Hidden amongst this is a potential time-bomb for radio amateurs. The French administration is effectively proposing that the 2 metre amateur band (144 - 146 MHz) which is currently allocated for the exclusive use by radio amateurs, should be shared with non-safety aeronautical mobile services. Note that this is already the case in China and that in Region 1 (Europe) the spectrum immediately below the 144 MHz band is already allocate for Aeronautical Mobile services. The proposal does not state whether the new allocation should be on a secondary basis (in which case radio amateurs would continue to be protected from interference) or whether it would be on a co-primary basis (in which case both sets of users would have equivalent interference protection rights).

Hidden amongst this is a potential time-bomb for radio amateurs. The French administration is effectively proposing that the 2 metre amateur band (144 - 146 MHz) which is currently allocated for the exclusive use by radio amateurs, should be shared with non-safety aeronautical mobile services. Note that this is already the case in China and that in Region 1 (Europe) the spectrum immediately below the 144 MHz band is already allocate for Aeronautical Mobile services. The proposal does not state whether the new allocation should be on a secondary basis (in which case radio amateurs would continue to be protected from interference) or whether it would be on a co-primary basis (in which case both sets of users would have equivalent interference protection rights).

Wireless Waffle understands that the proposal was originated by French defence manufacturer Thales, and that their preferred outcome would be a co-primary allocation. Should this happen, notwithstanding the fact that there would be an interferer in the 2 metre band, the aeronautical services, if they suffered interference from amateurs, could them potential claim protection. It is not completely impossible that as a result of this, the amateur service could be either reduced to secondary status, or told to leave the band. Such an outcome would take at least 12 years, as it would first have to be put on the agenda for a future WRC (which could not be until at least 2027), then studied, before a decision could be made (at the eariest 2031).

Should radio amateurs be concerned. In a word, YES! The 2 metre band is very heavily used and is one of the only primary and exclusive amateur radio allocations that exists. A number of other amateur bands have recently been reduced or lost to other services (e.g. 2.3 GHz, 3.4 GHz) and there is also consideration of removing the amateur service from the 23cm band from 1260 to 1300 MHz to protect satellite navigation systems. However inconceivable it may be that the 2 metre band could go the same way, it is not impossible.

What can radio amateurs do? It is the national radio spectrum administrations who attends the CEPT/ECC meetings and represents the views of their country. In the first instance, therefore, amateurs should write to their national regulator (e.g. Ofcom in the UK) and express the importance of keeping the 2 metre band primary and exclusive for amateur use.

What can radio amateurs do? It is the national radio spectrum administrations who attends the CEPT/ECC meetings and represents the views of their country. In the first instance, therefore, amateurs should write to their national regulator (e.g. Ofcom in the UK) and express the importance of keeping the 2 metre band primary and exclusive for amateur use. International organisations such as the IARU and national organisations such as the RSGB get involved to support the interests of radio amateurs, but this can only succeed if the national administrations listen empathetically.

If national administrations fail to support the amateur service, the next step would probably be for radio amateurs to protest outside CEPT/ECC meetings to try and demonstrate to CEPT just how strongly they object.

Conduct a web-search for topics relating to 5G and on many occasions the answers which get returned are nothing to do with the next generation of mobile services, but relate to 5 GHz, which is one of the frequency bands used for WiFi (as well as several other technologies). It seems that both terms being of a wireless nature, those clever search engines are yet to be able to fully distinguish between them.

Conduct a web-search for topics relating to 5G and on many occasions the answers which get returned are nothing to do with the next generation of mobile services, but relate to 5 GHz, which is one of the frequency bands used for WiFi (as well as several other technologies). It seems that both terms being of a wireless nature, those clever search engines are yet to be able to fully distinguish between them.But there is more... If that isn't confusing enough, there's also a technology known as G5 which is designed to perform the job of allowing vehicles to communicate with each other, known as vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) communications, and with infrastructure (such as traffic lights) known as V2I. And to really throw the cat amongst the pigeons, the frequency band used for G5 is 5 GHz (5850 - 5929 MHz). Got that?

So, just to be really clear and helpful in exactly the way that Wireless Waffle always isn't, here are some bullet points which don't make everything far more translucent:

So, just to be really clear and helpful in exactly the way that Wireless Waffle always isn't, here are some bullet points which don't make everything far more translucent:- 5G is the term used for the next generation of mobile technologies which will follow after 4G (LTE). The technology involved is also known as New Radio (NR).

- 5 GHz is a range of radio frequencies often considered as being 5150 - 5925 MHz, which are used by a wide variety of applications including WiFi, 4G (including LTE-U, LTE-LAA and MulteFire) and G5.

- G5 is a vehicle communication technology designed to enable Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) such as autonomous vehicles.

Friday 8 March, 2019, 13:10 - Broadcasting, Licensed, Radio Randomness, Spectrum Management

Posted by Administrator

A while ago Wireless Waffle added an FM DX logbook listing reception of far distant (a.k.a. DX) FM radio stations which have been received in the UK at various times. Reception of such stations has also been discussed before in particular with reference to sporadic-E propagation. Posted by Administrator

FM stations being received over a long distance by sporadic-E tend to be very strong, and can often overwhealm reception of local stations. Those being received through tropospheric ducting are often somewhat weaker.

It was a surprise, therefore, on a recent drive around London's orbital motorway, the M25, whilst listening to community station Kane FM at a distance of approximately 13 km from the transmitter, that french station France Inter on the same frequency of 103.7 MHz, became stronger. So much so, that the radio in the car decoded the RDS of France Inter and switched between 103.7 and 99.6 MHz where a second transmitter could be received.

It was a surprise, therefore, on a recent drive around London's orbital motorway, the M25, whilst listening to community station Kane FM at a distance of approximately 13 km from the transmitter, that french station France Inter on the same frequency of 103.7 MHz, became stronger. So much so, that the radio in the car decoded the RDS of France Inter and switched between 103.7 and 99.6 MHz where a second transmitter could be received.  The transmitter of France Inter on 103.7 MHz uses a massive power of 400 kW from a site in Lille (approximately 260 km away). It is actually one of the highest powered FM transmitters in the whole of Europe. The France Inter transmitter on 99.6 MHz uses a transmitter power of 50 kW from a site in Caen (approximately 225 km away). If you consider the free space path loss from these sites, and their transmitter power, you can roughly calculate the expected signal strength that each transmitter would produce.

The transmitter of France Inter on 103.7 MHz uses a massive power of 400 kW from a site in Lille (approximately 260 km away). It is actually one of the highest powered FM transmitters in the whole of Europe. The France Inter transmitter on 99.6 MHz uses a transmitter power of 50 kW from a site in Caen (approximately 225 km away). If you consider the free space path loss from these sites, and their transmitter power, you can roughly calculate the expected signal strength that each transmitter would produce.| Radio Station | Frequency | Power | Distance | Path Loss | Field Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kane FM | 103.7 | 25 W | 13 km | 95 dB | 56 dBuV/m |

| France Inter (Lille) | 103.7 | 400 kW | 260 km | 121 dB | 72 dBuV/m |

| France Inter (Caen) | 99.6 | 50 kW | 225 km | 120 dB | 64 dBuV/m |

Assuming free space loss, therefore, the signals from France would be 8 to 16 dB higher than those from the nearby Kane FM transmitter.

However, this is nothing like reality: free space path loss gives a result which would represent the strongest possible signal that could be received. Of course none of the signals would be propagating in this way, as there would be innumerable obstacles along the way that would deviate wildly from 'free space' and the signals would come nowhere near these values, especially those that have travelled 200 km or more from France. Note that various studies have indicated that for reception in a car, a signal strength around 40 dBuV/m is needed suggesting that the additional path loss caused by propagation effects would have been in the order of 16 to 32 dB, which seems reasonable.

FM receivers have an effect called the 'capture ratio'. In general, if two signals are on the same frequency, and one is more than around 3 dB stronger than the other, then the strongest signal will win-out and the weaker one will disappear. So at least it is clear that the signal from France Inter on 103.7 was a few dB stronger from that of Kane FM.

None of this is groundbreaking nor even necessarily that interesting, but it does suggest that the actual path loss obtained during reception by tropospheric ducting can be relatively low. And for radio stations in areas prone to tropospheric ducting (predictions of which can be found on Willam Hepburn's excellent web-site), using a few extra dB of transmitter power may be necessary to ensure reliable reception. Stations, for example, on either side of the Arabian Gulf often use tens of kiloWatts of transmitter power even to provide coverage of just one city, as problems with ducting of signals from the other side of the Gulf are an almost daily occurrence.

Of course, the converse is that using more power then causes increased interference to those on the other end of the duct. Which in turn requires them to turn up their power to combat the problem. Which makes the problem worse. And so forth...