Wednesday 18 August, 2021, 09:35 - Broadcasting, Licensed, Radio Randomness, Spectrum Management

Posted by Administrator

For some time, Wireless Waffle has published an FM DX Logbook. This logbook records any DX (distance) reception of FM broadcast stations that have been received, through whatever means (i.e. home FM tuner, car radio, software radio). Though an interesting exercise in itself, a recent update to the page to show the propagation mode which has been used also included some simple calculations to show the number of metres travelled divided by the number of Watts of transmitter power, and an additional calculation working out what the received signal power would be, assuming free space path loss between the transmitting and receiving location.Posted by Administrator

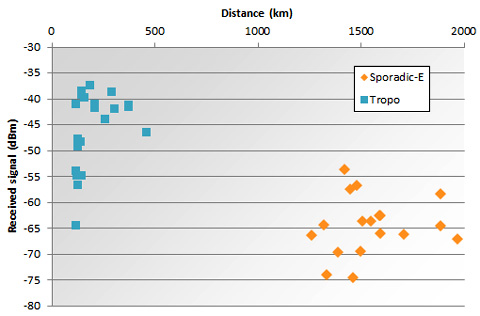

The use of free space path loss as the propagation model is definitely not applicable for any mode of propagation other than line-of-sight but it proved to be a useful exercise. Based on the frequency and power of the transmitter, and the length of the path, it is possible to determine how strong the received signal would be, if the path was line-of-sight. The results show an interesting trend.

With the exception of a few shorter paths (up to about 150 km), the theoretical signal strengths received from broadcasts received via troposhperic propagation are clustered around -40 dBm (which equates to about 67 dBuV/m). Similarly, the theoretical signal strength of transmissions received via Sporadic-E propagation are clustered around -65 dBm (42 dBuV/m). Note that these are not measured signal strengths, but a calculation of how strong the signals would be if they were being received via a line-of-sight path - which they are not.

A previous Wireless Waffle article identified that around 40dBuV/m is required at a receiver for FM reception. It is almost certainly true, that in the case of both the DX reception via the troposphere, or via Sporadic-E, the actual received signal strength would be similar, as in both cases the signal would need to be strong enough to be successfully received: the necessary signal would be nearer the -65 dBm level than the -40 dBm level. If this is true, then it must also be true that the additional loss caused by a signal travelling via ducts in the troposphere compared to via ionised clouds in the E-layer is around 25 dB, as this is the additional loss which the signal could tolerate and still be received.

This just goes to show how effective Sporadic-E propagation is and why it is (or indeed was) such a problem for VHF television and radio broadcasters during the summer months when it is most prevalent. It also suggests that the path loss via Sporadic-E must be close to the free space value, as if the received signal strength is around 42 dBuV/m based on free space path loss, this is only a couple of dB different to that needed for successful reception and the actual path could not be introducing much in the way of additional attenuation.

add comment

( 184 views )

| permalink

|

( 2.6 / 930 )

( 2.6 / 930 )

( 2.6 / 930 )

( 2.6 / 930 )

Though it may have passed most of the international news channels by, the world's radio spectrum regulators and associated government departments and ministers have just signed away the results of the 2019 World Radiocomminication Conference (WRC-19) held in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. This 4 week long event is where international decisions on the use of the radio spectrum take place. Or at least that's the theory. All 'decisions' have to be driven by consensus, which means that everyone must agree and with so many divergent views on topics as wide ranging as more spectrum for 5G mobile services, to globally harmonising spectrum for railway communications, there is lots to discuss. There were around 20 items on the agenda for the conference.

Though it may have passed most of the international news channels by, the world's radio spectrum regulators and associated government departments and ministers have just signed away the results of the 2019 World Radiocomminication Conference (WRC-19) held in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. This 4 week long event is where international decisions on the use of the radio spectrum take place. Or at least that's the theory. All 'decisions' have to be driven by consensus, which means that everyone must agree and with so many divergent views on topics as wide ranging as more spectrum for 5G mobile services, to globally harmonising spectrum for railway communications, there is lots to discuss. There were around 20 items on the agenda for the conference.Of particular interest to radio amateurs was agenda item 1.1, which concerned:

the allocation of the frequency band 50-54 MHz to the amateur service in Region 1

Radio amateurs have requested that the whole frequency range from 50 to 54 MHz is allocated to them on a primary basis in ITU Region 1 which is Europe, the Middle East and Africa. At present, in the ITU Radio Regulations, which dictate which frequencies are allocated to which services, 50 - 54 MHz is allocated to radio amateurs on a primary basis in Regions 2 (the Americas) and 3 (Asia/Pacific), and the idea was to align the band in every region. In Region 1 the frequencies are allocated to broadcasting as well as (in some countries) to radiolocation, land mobile and fixed (point-to-point) services, but not to radio amateurs (unless national administrations have unilaterally decided to allow them). Only in Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe does the band have any allocation to radio amateurs in the existing Radio Regulations.

Radio amateurs have requested that the whole frequency range from 50 to 54 MHz is allocated to them on a primary basis in ITU Region 1 which is Europe, the Middle East and Africa. At present, in the ITU Radio Regulations, which dictate which frequencies are allocated to which services, 50 - 54 MHz is allocated to radio amateurs on a primary basis in Regions 2 (the Americas) and 3 (Asia/Pacific), and the idea was to align the band in every region. In Region 1 the frequencies are allocated to broadcasting as well as (in some countries) to radiolocation, land mobile and fixed (point-to-point) services, but not to radio amateurs (unless national administrations have unilaterally decided to allow them). Only in Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe does the band have any allocation to radio amateurs in the existing Radio Regulations.Following the machinations at WRC-19, the radio amateurs have been granted a secondary allocation across Region 1 in the frequency range 50 - 52 MHz, with primary allocations in some or all of the range 50 - 54 MHz in a limited number of new countries. A secondary allocation means that the amateurs must not cause interference to any primary services (i.e. broadcasting and land mobile) and must accept interference from them, but it's a step forwards towards a global expansion of the 6 metre band.

This does not mean that the band will be available in each and every country immediately. First, each country's administration or regulator needs to update their national frequency allocation table to include the new band. This can take anything from a few months to a few years. There are still some countries who have not yet implemented the results of the previous WRC in 2015, despite it being completed 4 years ago. So don't hold your breath hoping to use the band when on holiday in Ouagadougou, it may be a long time before this new band is widely available.

The next task for the International Amateur Radio Union (IARU) who work tirelessly on behalf of radio amateurs at events such as WRC-19 is to deal with Agenda Items 1.2 and 9.1.2 of the next WRC in 2023. Agenda Item 1.2 is entitled:

The next task for the International Amateur Radio Union (IARU) who work tirelessly on behalf of radio amateurs at events such as WRC-19 is to deal with Agenda Items 1.2 and 9.1.2 of the next WRC in 2023. Agenda Item 1.2 is entitled:to consider identification of the frequency bands ... 10.0-10.5 GHz for International Mobile Telecommunications (IMT), including possible additional allocations to the mobile service on a primary basis... (N.B. this applies in Region 2, i.e. the Americas, only)

This includes a secondary Amateur allocation between 10.0 and 10.5 GHz, and a secondary Amateur-Satellite allocation between 10.45 and 10.5 GHz (as used by the already infamous Es'Hail-2 (a.k.a. QO-100), the first geostationary satellite with an Amateur radio transponder. Whilst the allocation of the band for IMT (5G) services does not preclude the Amateur service, in reality, a band full of a dense network of base stations and handsets would make it nigh-on impossible to be used for amateur radio and the band may be lost, in exactly the same way that the 2.3 GHz and 3.4 GHz bands were.

Agenda Item 9.1.2 is entitled:

Review of the amateur service and the amateur-satellite service allocations in the frequency band 1 240-1 300 MHz to determine if additional measures are required to ensure protection of the radionavigation-satellite (space-to-Earth) service operating in the same band...

The IARU will need to stave off pressure to remove (or otherwise reduce) the radio amateur secondary allocation on the frequencies 1240 - 1300 MHz (the 23 cm band) as it is claimed by the European Commission that amateurs may cause interference to their Galileo satellte navigation system. Not, it is worth pointing out, the everyday service used by smart phones and in-car sat-navs, but an additional service for specialist users.

The IARU will need to stave off pressure to remove (or otherwise reduce) the radio amateur secondary allocation on the frequencies 1240 - 1300 MHz (the 23 cm band) as it is claimed by the European Commission that amateurs may cause interference to their Galileo satellte navigation system. Not, it is worth pointing out, the everyday service used by smart phones and in-car sat-navs, but an additional service for specialist users.  The argument goes that there was once an amateur television repeater in the band which caused interference. Once - and it was resolved very quickly. But that is enough to raise concerns of potential wider future interference problems. The Commission therefore want to throw the amateurs out of the spectrum. The amateur allocation is secondary, so they must not cause interference, and so the Galileo service is already protected, but that is not always enough for everyone. The ITU giveth with one hand, and threaten to take away with two others. Was it ever any different?

The argument goes that there was once an amateur television repeater in the band which caused interference. Once - and it was resolved very quickly. But that is enough to raise concerns of potential wider future interference problems. The Commission therefore want to throw the amateurs out of the spectrum. The amateur allocation is secondary, so they must not cause interference, and so the Galileo service is already protected, but that is not always enough for everyone. The ITU giveth with one hand, and threaten to take away with two others. Was it ever any different?Friday 15 November, 2019, 06:15 - Spectrum Management, Much Ado About Nothing

Posted by Administrator

Posted by Administrator

Over 1000 delegates are currently slogging it out at the World Radiocomminication Conference taking place in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. The conference can be extremely tedious as various working groups sit in laborious meetings working out whether 'and' or 'or' should be used in a sentence.

Over 1000 delegates are currently slogging it out at the World Radiocomminication Conference taking place in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. The conference can be extremely tedious as various working groups sit in laborious meetings working out whether 'and' or 'or' should be used in a sentence.To try and help with the boredom, Wireless Waffle presents, ITU WRC Bingo.

The rules are very simple. Whilst sitting in a meeting, every time that a word on your bingo card is spoken, click on it and it will be illuminated. If you get 5 words in a row (vertically, horizontally, or diagonally) you have achieved BINGO! At this point, the rules require you to stand up and shout either 'bingo' or 'house' but perhaps you might wish, instead, to ask the chairman for the floor and quietly state:

Subject to confirmation by the sub-working group, and noting the necessary primary resolution, I resolve to believe that the correct terminology for that which is in front of me, is 'Bingo'!

A lot of countries are beginning to consider the use of what is known as 'C-band' for new 5G services. The C-band runs from 3400 - 4200 MHz and is a set of radio frequencies extensively used for satellite connections (and for some point-to-point fixed links and the odd point-to-multipoint network). The satellite uses connections fall into a number of categories:

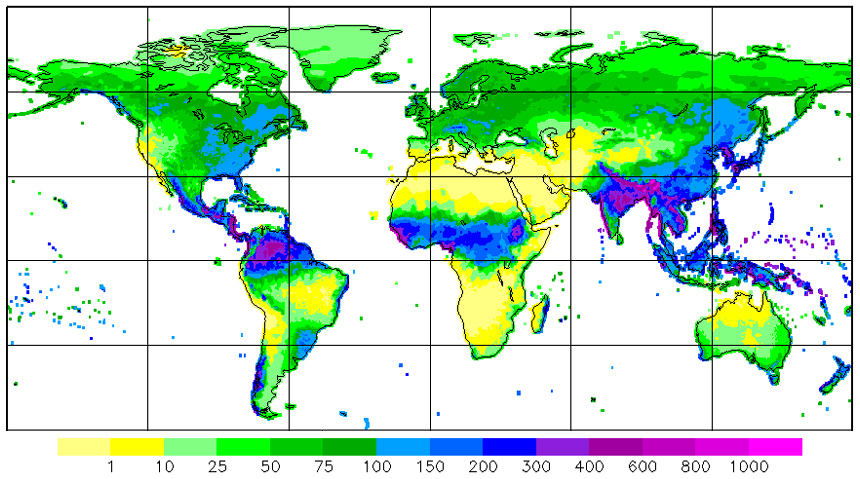

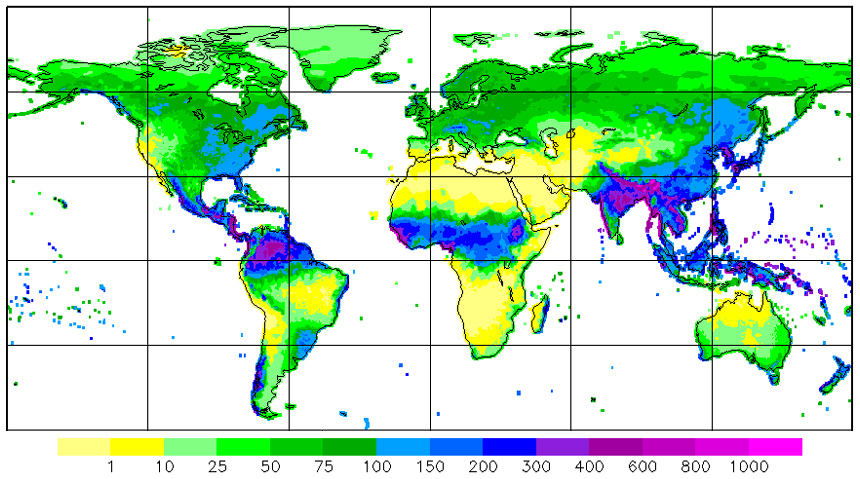

As can be seen from the map above (click for a bigger version), there is a swathe of the world, primarily in equatorial areas, where it really rains (those in blue and purple). In these areas, signals in other satellite frequency bands, such as Ku-band (11 GHz) and Ka-band (20 GHz) are absorbed so much by rain that when it pours, they become unreceivable but C-band being a lower frequency (4 GHz) does not. Using the band for 5G in countries where C-band is only lightly used is not impossible. Though 5G transmissions can wipe-out satellite reception in areas hundreds of kilometers from the 5G base stations, very careful planning of frequencies and site placements can lead to some solutions.

In countries, however, where there are hundreds of VSAT terminals, or thousands of domestic satellite receivers, the situation is more bleak. There is fundamentally no way that 5G networks and satellite receivers can share the same frequencies. The transmitter power of a satellite is not completely dissimilar to that of a 5G base station, but one is 40,000 kilometers away and the other may be 40 metres away. Clearly one will enormously overshadow the other.

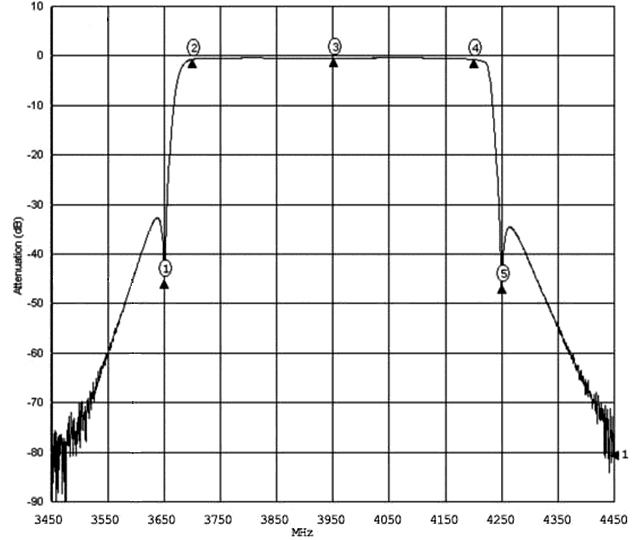

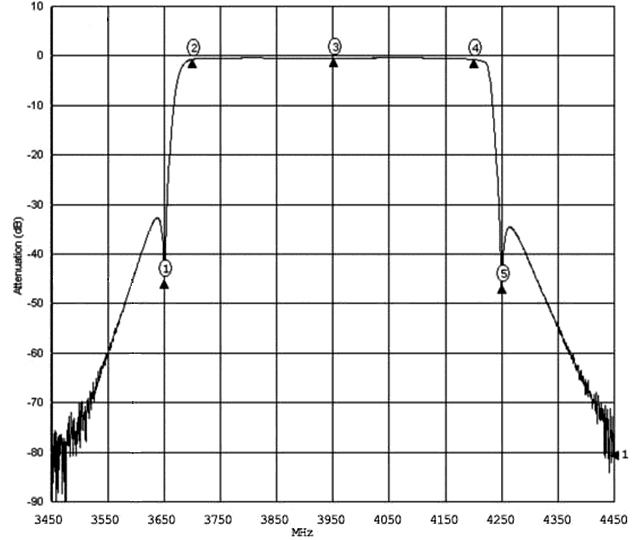

The only way that the two services can therefore co-exist is to separate the 5G frequencies from those used for satellite reception. As there are no 'unused' satellite frequencies in the C-band, this means that regulators have to take a decision to slice up the band, taking spectrum away from satellites and giving it to 5G services and this is what many have done. Hong Kong, Cambodia, Singapore and the Philippines (to mention a few) have decided to use frequencies from 3400 - 3600 MHz for 5G services, and leave 3700 - 4200 MHz for satellite services. The gap in-between (3600 - 3700 MHz) is left as a guard-band, a kind of no-mans-land in which neither service has priority. This allows satellite receivers to be fitted with filters which allow signals above 3700 MHz through, whilst rejecting signals below 3600 MHz (see the example on the right).

As there are no 'unused' satellite frequencies in the C-band, this means that regulators have to take a decision to slice up the band, taking spectrum away from satellites and giving it to 5G services and this is what many have done. Hong Kong, Cambodia, Singapore and the Philippines (to mention a few) have decided to use frequencies from 3400 - 3600 MHz for 5G services, and leave 3700 - 4200 MHz for satellite services. The gap in-between (3600 - 3700 MHz) is left as a guard-band, a kind of no-mans-land in which neither service has priority. This allows satellite receivers to be fitted with filters which allow signals above 3700 MHz through, whilst rejecting signals below 3600 MHz (see the example on the right).

In such a scenario, there is still potential for interference to the satellite services in two possible ways:

The solution to this, would be to fit filters to the 5G transmitters to reduce the unwanted emissions, but this costs the mobile operators and they are not keen to do so. In some cases they are not even able to do so. The use of 'massive MIMO' antennas means that the transmitters and antennas are incorporated into a single unit, inside which there is no room to fit a filter.

The solution to this, would be to fit filters to the 5G transmitters to reduce the unwanted emissions, but this costs the mobile operators and they are not keen to do so. In some cases they are not even able to do so. The use of 'massive MIMO' antennas means that the transmitters and antennas are incorporated into a single unit, inside which there is no room to fit a filter.

Sharing of the C-band between satellite services and 5G networks therefore remains a thorny issue and it will be interesting to see how the problem is resolved. One option is, of course, to use a different band in areas where C-band satellite is in strong demand. The 2.6 GHz band (2500 - 2690 MHz) is currently built in to every 5G phone that is on the market and in the near future the millimetre wave bands (26 GHz and above) will form part of the ecosystem, so maybe the satellite operators will be left alone in their C-band spectrum in places where it never rains, but it pours.

- Lifeblood links for remote areas (including some countries whose only international connection is via satellite such as Ascension Island).

- VSAT connections for businesses (i.e. banks and petrol stations) and for remote internet connections.

- Domestic television reception.

As can be seen from the map above (click for a bigger version), there is a swathe of the world, primarily in equatorial areas, where it really rains (those in blue and purple). In these areas, signals in other satellite frequency bands, such as Ku-band (11 GHz) and Ka-band (20 GHz) are absorbed so much by rain that when it pours, they become unreceivable but C-band being a lower frequency (4 GHz) does not. Using the band for 5G in countries where C-band is only lightly used is not impossible. Though 5G transmissions can wipe-out satellite reception in areas hundreds of kilometers from the 5G base stations, very careful planning of frequencies and site placements can lead to some solutions.

In countries, however, where there are hundreds of VSAT terminals, or thousands of domestic satellite receivers, the situation is more bleak. There is fundamentally no way that 5G networks and satellite receivers can share the same frequencies. The transmitter power of a satellite is not completely dissimilar to that of a 5G base station, but one is 40,000 kilometers away and the other may be 40 metres away. Clearly one will enormously overshadow the other.

The only way that the two services can therefore co-exist is to separate the 5G frequencies from those used for satellite reception.

As there are no 'unused' satellite frequencies in the C-band, this means that regulators have to take a decision to slice up the band, taking spectrum away from satellites and giving it to 5G services and this is what many have done. Hong Kong, Cambodia, Singapore and the Philippines (to mention a few) have decided to use frequencies from 3400 - 3600 MHz for 5G services, and leave 3700 - 4200 MHz for satellite services. The gap in-between (3600 - 3700 MHz) is left as a guard-band, a kind of no-mans-land in which neither service has priority. This allows satellite receivers to be fitted with filters which allow signals above 3700 MHz through, whilst rejecting signals below 3600 MHz (see the example on the right).

As there are no 'unused' satellite frequencies in the C-band, this means that regulators have to take a decision to slice up the band, taking spectrum away from satellites and giving it to 5G services and this is what many have done. Hong Kong, Cambodia, Singapore and the Philippines (to mention a few) have decided to use frequencies from 3400 - 3600 MHz for 5G services, and leave 3700 - 4200 MHz for satellite services. The gap in-between (3600 - 3700 MHz) is left as a guard-band, a kind of no-mans-land in which neither service has priority. This allows satellite receivers to be fitted with filters which allow signals above 3700 MHz through, whilst rejecting signals below 3600 MHz (see the example on the right).In such a scenario, there is still potential for interference to the satellite services in two possible ways:

- strong signals from the 5G transmitters can overload the satellite receivers (even after the rejection provided by the filter); or

- unwanted emissions from the 5G transmitters on the frequencies being received by the satellites can cause interference.

The solution to this, would be to fit filters to the 5G transmitters to reduce the unwanted emissions, but this costs the mobile operators and they are not keen to do so. In some cases they are not even able to do so. The use of 'massive MIMO' antennas means that the transmitters and antennas are incorporated into a single unit, inside which there is no room to fit a filter.

The solution to this, would be to fit filters to the 5G transmitters to reduce the unwanted emissions, but this costs the mobile operators and they are not keen to do so. In some cases they are not even able to do so. The use of 'massive MIMO' antennas means that the transmitters and antennas are incorporated into a single unit, inside which there is no room to fit a filter.Sharing of the C-band between satellite services and 5G networks therefore remains a thorny issue and it will be interesting to see how the problem is resolved. One option is, of course, to use a different band in areas where C-band satellite is in strong demand. The 2.6 GHz band (2500 - 2690 MHz) is currently built in to every 5G phone that is on the market and in the near future the millimetre wave bands (26 GHz and above) will form part of the ecosystem, so maybe the satellite operators will be left alone in their C-band spectrum in places where it never rains, but it pours.