Wednesday 27 February, 2013, 08:20 - Amateur Radio, Spectrum Management, Satellites

Posted by Administrator

Over in Brussels, the European Commission, through the direction given to it by the Radio Spectrum Policy Programme (RSPP), is trying to identify 1200 MHz of spectrum that can be made available for 'wireless broadband' services. At present there is 1025 MHz of spectrum available for such services including:Posted by Administrator

| Band | Allocation | Total Spectrum |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Dividend | 791 – 821 // 832 – 862 MHz | 60 MHz |

| 900 MHz | 880 – 915 // 925 – 960 MHz | 70 MHz |

| 1800 MHz | 1710 – 1785 // 1805 – 1880 MHz | 150 MHz |

| 2.1 GHz (FDD) | 1920 – 1980 // 2110 – 2170 MHz | 120 MHz |

| 2.1 GHz (TDD) | 1900 – 1920 MHz 2010 – 2025 MHz |

35 MHz |

| 2.6 GHz (FDD) | 2500 – 2570 // 2620 – 2690 MHz | 140 MHz |

| 2.6 GHz (TDD) | 2570 – 2620 MHz | 50 MHz |

| 3.6 GHz | 3400 – 3800 MHz | 400 MHz |

| Total | 1025 MHz | |

Finding another 175 MHz to make the goal of 1200 MHz is therefore surely not such a big ask. However, there are issues with the spectrum that is currently available. The 3400 – 3800 MHz band accounts for 400 MHz or a good third of it and despite already being allocated to broadband wireless in Europe, it has not been very popular. The slow take-up is partly due to a lack of mass market products for the band and the poorer propagation at these higher frequencies, but is also due to the need to protect certain C-Band satellite downlinks which remain in the band. This also forms the 9cm amateur band. It therefore seems sensible that if new spectrum is to be found, it ought to be below 3 GHz in order that it will prove popular enough to actually be put into use.

To try and identify 'underused' spectrum, the European Commission is conducting a spectrum inventory whose purpose is to firstly examine the availability and use of spectrum and then to consider the future needs to try and match supply with demand. The first part of this inventory, a study which examined the extent to which each spectrum band is used was published in late 2012. The initial findings of the consultants who undertook the study were that the bands with the lowest current usage and thus which might be candidates for re-allocation were:

To try and identify 'underused' spectrum, the European Commission is conducting a spectrum inventory whose purpose is to firstly examine the availability and use of spectrum and then to consider the future needs to try and match supply with demand. The first part of this inventory, a study which examined the extent to which each spectrum band is used was published in late 2012. The initial findings of the consultants who undertook the study were that the bands with the lowest current usage and thus which might be candidates for re-allocation were:- 1452 – 1492 MHz. This band is set aside for DAB radio services, however it has remained virtually unused. The ECC have now recommended the re-allocation of this band for mobile services after pressure from Ericsson and Qualcomm to do so. This is therefore a 'no brainer' or a 'done deal'.

- 1980 – 2010 // 2170 – 2200 MHz. This band is currently allocated for 3G mobile satellite services to complement terrestrial 3G services. One satellite (Eutelsat 10A) was launched with a payload that is active in this band, but it failed to deploy the dish correctly and as such the band remains largely (though not completely) unused. It would seem churlish to take this away though, when there is still scope for it to be commercialised for its intended purpose. Perhaps some form of sharing using a complimentary ground component could be envisaged.

- 3400 – 3800 MHz. This was identified as being underused… 'Quelle surprise' as they say in Brussels!

- 3800 – 4200 MHz. This is also part of the C-Band satellite downlink frequency range but has also been used for fixed links in some countries. Fixed links can be carefully controlled so as to avoid interference to satellite ground stations: it is unclear how a more widespread roll-out of services in this band would be feasible. This also fails the 'below 3 GHz' test.

- 5030 – 5150 MHz. This band is allocated for aeronautical use and was intended to be used for a new microwave landing system (MLS) to replace existing landing systems and for aeronautical mobile satellite services (AMSS). Very few airports or airlines have adopted MLS (London Heathrow and British Airways being two of the few who have done so) and no AMSS services in the band have been launched. If 3.5 GHz is not popular though, it seems unlikely that 5 GHz will be any more welcome.

- 5725 – 5875 MHz. This is a band which is available on either a licence exempt or a lightly licensed basis in most European countries for use with WiFi (802.11a) and other low power services. Being well over 3 GHz it is unlikely to be popular. It also forms a large chunk of the 6cm amateur band.

One option on the table, though not identified through the inventory, is the frequency band 2300 – 2400 MHz. It was identified at the 2007 World Radio Conference as a candidate for IMT (the ITU code for wireless broadband). It is already in the 3GPP standards for LTE, where it is known as the mysterious 'Band 40'. The ECC has considered the use of this band for wireless broadband services and concluded that it is quite possible. Sweden and Australia have already handed all of the band over to wireless broadband use, and many other countries (especially in Asia) have licensed part of it. One of the big problems with this band in Europe is that it is heavily used by governmental (read 'defence') services who are already smarting from the loss of many other bands over the past years and are in no mood for another re-farming exercise to release this band. Oh, and it represents the vast portion (and the most useful bit) of the 13cm amateur band.

Meanwhile, over in the USA, the FCC has also recently assessed the possibility of reallocating some the frequency band 1675 -1710 MHz for wireless broadband uses. This band is currently used for the downlink for meteorological satellite services, however few satellites venture above 1695 MHz (with the possible exception of a couple of NOAA satellites, the Chinese Feng Yun satellites and the polar orbiting METOP) and there is almost nothing above 1700 MHz, unless you count satellites yet to be launched (such as GOES-R).

Meanwhile, over in the USA, the FCC has also recently assessed the possibility of reallocating some the frequency band 1675 -1710 MHz for wireless broadband uses. This band is currently used for the downlink for meteorological satellite services, however few satellites venture above 1695 MHz (with the possible exception of a couple of NOAA satellites, the Chinese Feng Yun satellites and the polar orbiting METOP) and there is almost nothing above 1700 MHz, unless you count satellites yet to be launched (such as GOES-R).Given the location of this spectrum, directly adjacent to the existing 1800 MHz band, and given that the associated pairing is also largely unused it might easily be possible to, say, extend the 1800 MHz band by 2 x 10 to become 1700 – 1785 // 1795 – 1880 MHz. Keeping the spacing between the up and downlinks would simplify the adoption of the new spectrum (in the same way that GSM became E-GSM). The 10 MHz gap in the middle is rather small which can cause handset manufacturers problems, but there are ways this could be dealt with. The loser here (other than some yet-to-be-launched satellites who could surely locate their downlink in the remaining part of the band) are radiomicrophones who are allocated 1785 – 1800 MHz. A screaming case of 'use it or lose it' if they are to retain this allocation.

And whilst we're pairing up things, how's about extending the 2.1 GHz band? The lower part of the pair, 1900 – 1920 MHz, is already licensed, albeit for TDD services. The upper part of the pair, 2090 – 2110 MHz is another of those military bands that would prove difficult to squeeze. The bigger problem here is that it contains sensitive satellite uplinks that are easily interfered with. Nonetheless, there was a terrestrial wireless network licensed in the band in the UK (Zipcom), if never actually launched.

So far, we have identified the following extra spectrum:

| Band | Allocation | Total Spectrum |

|---|---|---|

| L-Band | 1452 – 1492 MHz | 40 MHz |

| Extended 1800 MHz | 1700 – 1710 // 1795 – 1805 MHz | 20 MHz |

| Extended 2.1 GHz | 1900 – 1920 // 2090 – 2110 MHz | 20 MHz (20 MHz was already available) |

| 2.1 GHz MSS sharing | 1980 – 2010 // 2170 – 2200 MHz | 60 MHz (shared with satellite) |

| 2.3 GHz | 2300 – 2400 MHz | 100 MHz |

| Total | 240 MHz | |

That makes 240 MHz of potential new sub-3 GHz spectrum without too much pain and done in a way that is largely compatible with existing mobile bands, though not with existing defence or satellite sensitivities. Given the recent auction prices for spectrum, 240 MHz across Europe is worth something in the region of 75 billion Euro. So what would it cost to release it?

- L-Band is free in every sense of the word. Except possibly in the UK where it is owned by Qualcomm but presumably as they have been lobbying for it to become available for mobile services, they would have no qualms about using it for such. Cost: peanuts.

- Extended 1800 MHz The main affected party here are some meteorological satellite downlink sites. These are few and far between and could be protected through the use of an exclusion zone. Cost: cashew nuts.

- Extended 2.1 GHz The number of military satellites using the band 2090 – 2110 MHz is difficult to ascertain (for obvious reasons). There is also a need to re-farm the band 1900 – 1920 MHz. Cost: macadamia nuts.

- 2.1 GHz MSS sharing In theory there is nothing to stop this taking place even with a satellite already launched. To be completely fair, it would only be reasonable to recompense the licensees (Solaris and Intelsat) for their investments. Cost: pistachio nuts.

- 2.3 GHz Those defence boys have big toys (and big guns) that would be costly to replace. That being said, only around 40 MHz of this band is necessary if the target is 175 MHz and not 240 MHz. Surely releasing 40 MHz can’t be that difficult no matter how big your toys. The fact that the band is destined for TDD means that it doesn’t even need to be the same 40 MHz in each country. Cost: pistachio nuts.

Alternatively, perhaps radio amateurs who stand to lose the 13cm, 9cm and 6cm bands might wish to launch a counter-bid? After all, they’re replete with nuts (in a good way)…!

add comment

( 2002 views )

| permalink

|

( 3.1 / 2385 )

( 3.1 / 2385 )

( 3.1 / 2385 )

( 3.1 / 2385 )

Wednesday 20 February, 2013, 10:29 - Spectrum Management

Posted by Administrator

Posted by Administrator

Ofcom has today published the long awaited outcome of the first phase of the UK 4G auction. The second phase of the auction is yet to take place. The first phase decided who gets how much of the spectrum, the second phase decides who gets which particular frequencies.

Ofcom has today published the long awaited outcome of the first phase of the UK 4G auction. The second phase of the auction is yet to take place. The first phase decided who gets how much of the spectrum, the second phase decides who gets which particular frequencies.The winning bidders, together with the total price they paid for the spectrum they have won are shown in the table below.

| Bidder | 800 MHz | 2.6 GHz (paired) |

2.6 GHz (unpaired) |

Price |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Everything Everywhere | 2 x 5 MHz | 2 x 35 MHz | £589 million | |

| Hutchison 3G | 2 x 5 MHz | £225 million | ||

| Niche Spectrum Ventures (BT) | 2 x 15 MHz | 1 x 20 MHz | £186 million | |

| Telefonica | 2 x 10 MHz | £550 million | ||

| Vodafone | 2 x 10 MHz | 2 x 10 MHz | 1 x 25 MHz | £791 million |

| Total | £2,341 million | |||

Can this tell us anything about how much was paid for each of the different flavours of spectrum? Not exactly, but using relatively straightforward schoolboy maths, it's possible to make a decent stab at the value of each type of spectrum (note that this is not 100% accurate but should be in the right ball park). The results are as follows:

| Band | 800 MHz | 2.6 GHz (paired) | 2.6 GHz (unpaired) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Price per MHz | £25.83 million | £4.72 million | £2.89 million |

| Amount Awarded | 60 MHz (2 x 30 MHz) |

140 MHz (2 x 70 MHz) |

45 MHz |

| Total | £1,550 million | £661 million | £130 million |

So how does it compare with the results of auctions in other countries? Yet another table shows the outcomes in a selected number of other large European countries. (An exchange rate of £1=€1.2 has been used for the conversion).

| Band | Price per MHz for 800 MHz | Price per MHz for 2.6 GHz (paired) | Price per MHz for 2.6 GHz (unpaired) |

|---|---|---|---|

| France | £36.6 million | £5.57 million | |

| Germany | £49.6 million | £1.53 million | £1.44 million |

| Italy | £41.1 million | £3.00 million | £2.06 million |

| UK | £25.8 million | £4.72 million | £2.89 million |

So the UK has not done as well for the 800 MHz spectrum (if you count 'doing well' as raising as much money as possible) compared to these other countries.

So the UK has not done as well for the 800 MHz spectrum (if you count 'doing well' as raising as much money as possible) compared to these other countries. Of course these results are only estimates inasmuch as the maths cannot be 100% accurate without more information, but nonetheless one thing that is certain is the auction has raised significantly less than the £4 billion that pundits were expecting. What will this mean for the UK? On the one hand the UK Government will have a larger hole in its budget than it would have hoped. On the other, perhaps we can expect cheaper 4G services and a faster roll-out than might have been expected. Maybe a victory for the consumer then? Or just the shareholders of the mobile companies?

One issue with WiFi that crops up regularly is that of selecting which channel to use. This is a subject on which several previous articles have been written, however the discovery of a 2004 paper by Cisco entitled 'Channel Deployment Issues for 2.4-GHz 802.11 WLANs', looks at whether or not it is possible to seat WiFi hotspots on neighbouring channels and the effect that channel separation has on performance. Though the paper is now nearly 10 years old, it remains one of the only references on the issue.

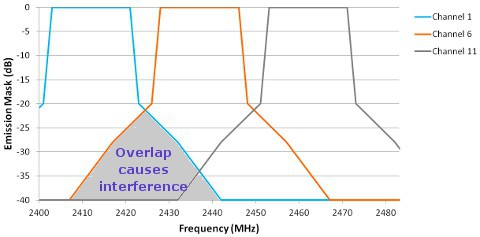

What the paper says, quite rightly, is that the extent to which a WiFi hotspot will cause interference to a neighbouring one is dependent on the extent to which interference from one is received by the other. This is partially a factor of the distance between them but is also related to their frequency separation. What the paper shows is that, in the USA, where there are 11 2.4 GHz WiFi channels available, only the set of channels 1, 6 and 11 are usable in such a way that a hotspot on one will not interfere with hotspots on the others. The paper examines what would happen if the set of channels 1, 4, 8 and 11 were used for four neighbouring hotspots. Cisco even did some tests which showed the following results:

| Channels Used | Throughput per Client |

|---|---|

| 1, 1, 6 and 11 | 601 KB/second |

| 1, 4, 8 and 11 | 349 KB/second |

What the results indicate is that even though, in the first test, two of the hotspots were on the same channel, the average throughput was increased over the four channel example because the overall level of interference was reduced. The paper also notes that WiFi hotspots on the same channel recognise each other and use various measures to try and avoid interfering whereas those on neighbouring channels just see interference on the channel. This is one reason why it is better to use a set group of channels in a given area (and to see what your neighbours are doing) rather than just pick a channel at random.

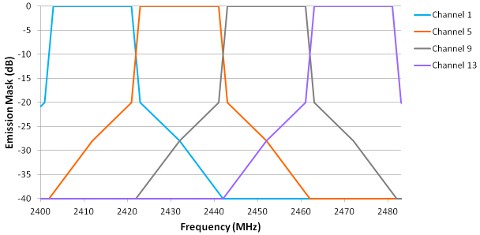

Having read this paper, the question that immediately arose was whether or not the fact that in Europe (and certain other parts of the world) there are 13 2.4 GHz WiFi channels available and not 11, offers up the possibility of a four channel arrangement that actually works - channels 1, 5, 9 and 13. The diagrams below show the emissions that are produced by the hotspots in the original three and proposed European four channel arrangements.

Three channel arrangement

Four channel arrangement

The amount of interference that is caused between devices is the overlapping area of the emissions of one transmitter with that of the receiver of a device on another channel (shown shaded on the first diagram). Using the standard emission mask to represent the emissions from one device (in reality they are usually lower than this) and using the same mask to represent the characteristics of the receiver of another (again a reasonable assumption) the extent to which a transmission on one channel is received by a receiver on another channel can be easily calculated.

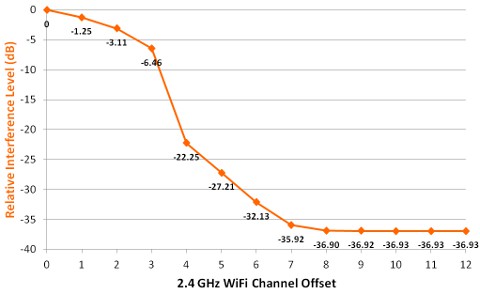

The chart below shows how much of the emissions of a transmitter on a given channel are received by a receiver which is offset by a certain amount from that channel.

An offset of zero means that both are on the same channel and therefore the interference is at 100% (shown as 0 dB). When the transmitter and receiver are separated by one channel (eg one hotspot is on channel 6, the other on channel 7), the amount of interference that one causes the other reduces by 1.25 dB (representing around 75% of the original value). When this offset is increased to two channels (eg one hotspot on channel 5, the other on channel 7), the interference falls by 3.1 dB (or around 50%). At the extreme, when the offset reaches 8 channels or more, the interference has fallen by nearly 37 dB (or to around 0.02% of the original value). So...

- In the case of the use of channels 1, 6 and 11 where the offset is 5 channels it can be seen that the level of mutual interference between hotspots would be -27 dB (or around 0.2%).

- In the case of the use of channels 1, 5, 9 and 13 where the offset is 4 channels it can be seen that the level interference between hotspots would be -22 dB (or around 0.6%).

- In the case of the use of channels 1, 4, 8 and 11 where the offset falls to 3 channels, the level interference between hotspots rises dramatically -6.4 dB (or around 23%).

It is therefore, perhaps, no great surprise that using the four channel arrangement posed by Cisco that interference levels increased to the point that the throughput dropped by nearly half. It does, however, look feasible that in Europe the use of a four channel arrangement that uses channels 1, 5, 9 and 13 might be feasible. A lot will depend on the characteristics of the receivers in use and whether they are as good as the emission mask.

Don't worry if you haven't understood everything presented here, the salient points are:

Don't worry if you haven't understood everything presented here, the salient points are:

- In the USA and other places where there are only 11 WiFi channels available, throughput will be maximised if everyone in the same neighbo(u)rhood stuck to using only channels 1, 6 or 11.

- In Europe and other places where there are 13 WiFi channels available, it seems quite feasible that if everyone sticks to using channels 1, 5, 9 or 13, the performance of everyone's WiFi hotspots would be maximised.

- Using a WiFi hotspot on a channel which is offset from a nearby hotspot by 1, 2 or 3 channels is a recipe for both hotspots to suffer interference and have degraded performance.

- Randomly picking a channel for your WiFi hotspot (eg. setting it to your lucky number) is a recipe for poor performance all round.

It is perhaps worth noting that in the 5 GHz band, no such restrictions apply as, sensibly, all of the available channels are mutually independent from all the others!

Unfortunately, unlike Cisco, the Wireless Waffle team do not have a shed full of WiFi hotspots that can be used to do tests on throughput. Perhaps someone might like to take up this challenge and let us know what the results are?

Monday 4 February, 2013, 05:57 - Spectrum Management

Posted by Administrator

Wireless Waffle has reported many times on the issue of jamming. Jamming, put simply, is the transmission of one radio signal in such a way as to intentionally block another one from being received. It is the intentional nature of jamming that distinguishes it from other kinds of radio interference. Posted by Administrator

Usually jamming is used for the purposes of disrupting something that the person doing the jamming does not wish to be received. Recently the BBC's satellite services have been jammed by both Syria and Iran who do not want the BBC's version of the news to reach their citizens. To this end, jammning is also illegal, as any kind of intentional radio interference usually is.

There are instances where jamming is sanctioned. In jails in some countries, for example, jammers which block cellular frequencies are used to stop inmates from using mobile phones to communicate to the outside world. Cellular jammers are also used in some mosques to ensure that peace and quiet is not disrupted by the 'Grande Valse'. It is believed that some theatres and cinemas also use cellular jammers to stop mobile phones spoiling the show. Unless explicit authority is gained fromt the regulator of the country concerned, though, the use of jammers, even where the purpose may seem harmless remains illegal. The illegality of jamming means that it is not usually advertised by those doing it.

So step forward chocolate bar Kit Kat who has established 'no WiFi' benches in the Dutch capital Amsterdam. At these benches WiFi is jammed with the idea being that you can go and sit on them and disconnect from the hecticities of daily life and 'have a break, have a Kit Kat'. An interesting question therefore arises as to whether the activities of Kit Kat are illegal or not. Whilst jamming per se is normally illegal, the bands in which WiFi operates (both 2.4 and 5 GHz) are licensed for many more services than just WiFi. In the 2.4 GHz band, for example, it is also legal to operate wireless video cameras, bluetooth, microwave ovens, cordless phones, remote control toys, and many more devices. Some of these devices would have the potential to knock-out WiFi links. CCTV cameras, for example, transmit a continuous signal which would do a good job of jamming WiFi and other services that were nearby.

So step forward chocolate bar Kit Kat who has established 'no WiFi' benches in the Dutch capital Amsterdam. At these benches WiFi is jammed with the idea being that you can go and sit on them and disconnect from the hecticities of daily life and 'have a break, have a Kit Kat'. An interesting question therefore arises as to whether the activities of Kit Kat are illegal or not. Whilst jamming per se is normally illegal, the bands in which WiFi operates (both 2.4 and 5 GHz) are licensed for many more services than just WiFi. In the 2.4 GHz band, for example, it is also legal to operate wireless video cameras, bluetooth, microwave ovens, cordless phones, remote control toys, and many more devices. Some of these devices would have the potential to knock-out WiFi links. CCTV cameras, for example, transmit a continuous signal which would do a good job of jamming WiFi and other services that were nearby.It would therefore be possible (and legal) to run a number of wireless cameras, on adjacent frequencies such that the whole 2.4 GHz band was jammed. Around 4 wireless cameras would be needed to do this. Now disconnect the camera and just put the transmitter in place and this remains legal (as it is the transmitter which is regulated, not the content). Lo and behold, it would be legally possible to jam all WiFi signals in a limited location. Whilst this is legal from an equipment perspective, whether or not doing this for the purpose of jamming WiFi rather than for transmitting video pictures opens up another legal issue. Article 15 of the ITU radio regulations says:

All stations are forbidden to carry out unnecessary transmissions, or the transmission of superfluous signals, or the transmission of false or misleading signals, or the transmission of signals without identification

Signals that were there for the purpose of stopping other signals being received would surely be 'superfluous'. In addition, article 45 of the ITU radio regulations states:

All stations, whatever their purpose, must be established and operated in such a manner as not to cause harmful interference to the radio services or communications of other Member States or of recognized operating agencies, or of other duly authorized operating agencies which carry on a radio service, and which operate in accordance with the provisions of the Radio Regulations

So if the purpose of running the wireless cameras was specifically to jam WiFi signals, and assuming that those WiFi signals were operating in accordance with the provision of the ITU Radio Regulations, they would remain illegal.

So if the purpose of running the wireless cameras was specifically to jam WiFi signals, and assuming that those WiFi signals were operating in accordance with the provision of the ITU Radio Regulations, they would remain illegal. Whether the Kit Kat 'WiFi free' areas are legal or not is therefore a subject that is, perhaps, open for discussion. Whether they are a good idea is equally subject to debate. Whether or not Kit Kat's are the right chocolate bar to have with a cup of tea (or coffee) during tea-breaks is, though, surely not a question that requires much debate. After all, they can't be all bad, if Cheryl Cole recommends them, right?