Monday 28 January, 2013, 12:22 - Licensed

Posted by Administrator

In a shock decision, Ofcom today announced that Arqiva are to run the UK's local television multiplex. The winning company, called 'Comux' has won the licence to operate the transmission network that will support local television services. Not speaking to Wireless Waffle, a spokesperson for Ofcom was overheard to think,Posted by Administrator

"We like Arqiva, oops, we mean Comux's proposal. After all, Arqiva transmit 'X-Factor' which brings us a lot of business in dealing with complaints: without Arqiva a lot of us would be out of a job. We also like the idea of supporting monopolistic companies that pay no corporation tax in the UK. We are hoping that Starbucks will bid in the 4G auction we are running at the moment and that Network Rail will bid to run a mobile network for trains (What? They already do? Since when?)"

But wait, in their public justification for the award, Ofcom state (page 6 of the account of decision),

But wait, in their public justification for the award, Ofcom state (page 6 of the account of decision),Arqiva is not an applicant for the licence...

So is Comux really Arqiva, that is the question. Well they certainly share the same postal address: Arqiva/Comux, Chalfont Grove, Chalfont St. Peter, Gerrards Cross SL9 8TW.

OK, it's not exactly conclusive but the fact that they share an office surely means there are opportunities for them to share a lot more too! Collusion is a very dirty word, almost as dirty as tax avoidance.

Either way, here's raising a glass at local television in the UK. Let's just hope they bring back Old Country with Jack Hargreaves. What? You mean he's already dead? Since when?

1 comment

( 3163 views )

| permalink

|

( 2.9 / 2036 )

( 2.9 / 2036 )

( 2.9 / 2036 )

( 2.9 / 2036 )

Wednesday 16 January, 2013, 03:58 - Broadcasting

Posted by Administrator

The UK public has been angered recently at the discovery that some high profile companies used various 'fiddles' to avoid paying tax. At a time when UK incomes have been squeezed, the idea that big name companies have not been contributing to the UK tax coffers left them hopping mad. The first company to be outed was Starbucks who, despite generating £400 million in revenues, paid less than three pence and a used muffin wrapper in corporation tax (corporation tax normally represents 20% of a company's profit).Posted by Administrator

Next up was Amazon whose sales in 2011 generated £3.35 billion yet who paid only £1.8 million in corporation tax. Even internet behemoth Google paid only £6 million in corporation tax against a turnover of £395 million.

These foreign companies largely argue that they pay tax elsewhere (presumably in countries where the tax burden is lower) and would end up being overcharged if they paid more in the UK. It should also not be forgotten that they generate VAT and pay income tax and national insurance for their employees, but nonetheless their tax affairs are more akin to the affairs in a bordello than those of honour.

But it seems that such activities are not just connected with foreign companies. Arqiva, the company responsible for transmitting all terrestrial television programmes across the UK (and many of the satellite programmes too) has, according to the Sunday Times, also been using some creative accounting to reduce its tax bill. The 'fiddle' they have employed is to get their parent companies (who are shareholders) to loan them money, but at a high interest rate, far above that which they would need to pay to take a loan at the bank. The repayments for these loans are taken from the accounts before dividends or the profit for tax purposes are calculated thus providing excellent returns to shareholders and also reducing Arqiva's corporation tax liability.

But it seems that such activities are not just connected with foreign companies. Arqiva, the company responsible for transmitting all terrestrial television programmes across the UK (and many of the satellite programmes too) has, according to the Sunday Times, also been using some creative accounting to reduce its tax bill. The 'fiddle' they have employed is to get their parent companies (who are shareholders) to loan them money, but at a high interest rate, far above that which they would need to pay to take a loan at the bank. The repayments for these loans are taken from the accounts before dividends or the profit for tax purposes are calculated thus providing excellent returns to shareholders and also reducing Arqiva's corporation tax liability.Arqiva's accounts show that shareholders took out £120m in 2012 and £106m in 2011 on loan interest charged at the stratospheric interest rate of 18%. Not quite Wonga.com interest rates but higher even than interest rates charged by car loan companies. As with Starbucks and Google, such fiddles are not illegal, but it could be argued that they are morally suspect, especially in the current financial climate. Arqiva are currently a monopoly provider and as such their fees are regulated. The regulated fees are based on their accounts, but such 'fiddles' would also impact the prices they charge. As their main customers include the BBC, UK citizens' licence fees are ending up in Arqiva's shareholders' pockets.

Arqiva would no doubt argue that as they do not make profits, they would not pay any corporation tax anyway. But they would be much closer to profitability if they weren't paying their owners for a loan at such extreme interest rates. What is certain is that their owners are benefiting from a much higher return on their investment than licence payers are!

Thursday 29 November, 2012, 04:07 - Licensed

Posted by Administrator

The local TV landscape in the UK is slowly taking shape as the decision on the final, and arguably the most commercially viable/advantageous franchises is delayed to give Ofcom more time to make the right decision. Whilst decisions on which companies will succeed in the lucrative markets of London, Leeds and Liverpool are still outstanding, also still to be announced is who will supply the transmission services for the local TV stations. Four bidders emerged when Ofcom invited tenders to deliver the local TV multiplexes:Posted by Administrator

Avanti Local TV (backed by broadband satellite company Avanti Communications – plans to use small transmitters to provide coverage tailored to local TV audiences)

Avanti Local TV (backed by broadband satellite company Avanti Communications – plans to use small transmitters to provide coverage tailored to local TV audiences) Comux UK (backed by Canis Media who run the local TV multiplex in Manchester – a group of consultants who will provide their expertise to local TV companies to help them get going)

Comux UK (backed by Canis Media who run the local TV multiplex in Manchester – a group of consultants who will provide their expertise to local TV companies to help them get going) LMux Ltd (backed by the BBC – will shepherd the roll-out of the network in good old BBC style, and keep it going with any available funds until such time as those funds run out)

LMux Ltd (backed by the BBC – will shepherd the roll-out of the network in good old BBC style, and keep it going with any available funds until such time as those funds run out) Local TV Multiplex Ltd (backed by the Community Media Association – will act as a central procurement facility to try and negotiate down prices of transmitters and other services for local TV companies)

Local TV Multiplex Ltd (backed by the Community Media Association – will act as a central procurement facility to try and negotiate down prices of transmitters and other services for local TV companies)The majority of the bidders will rely on existing television transmitter sites to provide the coverage for the local TV multiplexes. This has a number of advantages, not least that viewers’ TV antennas will be pointing in the right direction and (hopefully) will be of the correct antenna group to receive the transmissions. Historically, however, placing local television transmitters on larger transmitter towers has not necessarily offered an ideal solution.

Lanarkshire TV (LTV, later rebranded as Thistle TV) used the main Black Hill transmitter site situated between Glasgow and Edinburgh, both of which it covers. The old analogue TV transmissions on Black Hill used a power of 500 kW whereas LTV only had around 10kW of power. At 500 kW coverage of the region is excellent, at 10 kW (50 times or 17 dB less), coverage is marginal at best. Even close to the mast where the lower power signal is notionally strong enough to provide good reception, viewers receivers will be set up to receive the stronger signals (ie antennas will be of lower gain, or even indoor) and the large disparity in signal strength will render the lower power station largely unwatchable.

A similar (but worse) situation occurred on the Isle of Wight where not only was the local TV station Solent TV (and its predecessor TV12) using only 2 kW compared to the power of the main station of 250 kW but it was also on an ‘out of group’ channel.

The main transmitter at Rowridge uses channels at the lower end of the UHF TV band (channels 21 to 31 were used for analogue services), whereas Solent TV was on channel 54, meaning that not only was it 21 dB weaker leaving the transmitter due to its lower power (worse even than Lanarkshire TV) but the TV antennas of viewers (which are ‘grouped’ in order to focus their gain on the frequencies being used in the area) would add another 6 to 10 dB differential making the signals from Solent TV around 27-30 dB (500 to 1000 times) weaker than the main TV channels. The Solent TV transmitting aerials were also not as high up the mast as those of the main services, further reducing coverage. It is any wonder they went bust?

The main transmitter at Rowridge uses channels at the lower end of the UHF TV band (channels 21 to 31 were used for analogue services), whereas Solent TV was on channel 54, meaning that not only was it 21 dB weaker leaving the transmitter due to its lower power (worse even than Lanarkshire TV) but the TV antennas of viewers (which are ‘grouped’ in order to focus their gain on the frequencies being used in the area) would add another 6 to 10 dB differential making the signals from Solent TV around 27-30 dB (500 to 1000 times) weaker than the main TV channels. The Solent TV transmitting aerials were also not as high up the mast as those of the main services, further reducing coverage. It is any wonder they went bust?Arguably one of the more successful local TV stations (in terms of coverage) was Oxford TV (later known as Six TV).

The station was transmitted from the Oxford transmitter site which is, you might have guessed, relatively close to Oxford itself. Though the power was lower, it was ‘in-group’ and though the picture was not as good as the main services, most people in Oxford (and the surrounding area) could watch the programmes relatively happily.

The station was transmitted from the Oxford transmitter site which is, you might have guessed, relatively close to Oxford itself. Though the power was lower, it was ‘in-group’ and though the picture was not as good as the main services, most people in Oxford (and the surrounding area) could watch the programmes relatively happily.Under Ofcom’s proposals, local TV is once again being planned from sites such as Black Hill, this time using digital terrestrial (DTT) multiplexes. One of the advantages of DTT is that the modulation and error correction can be varied in order to allow weaker signals to have coverage that is on a par with stronger ones, at the expense of the amount of data they carry. It is proposed that the local TV multiplexes will use QPSK and 2/3 rate FEC giving a capacity of around 8 Mbit/s, enough for 3 standard definition (SD) pictures. Current multiplexes (ignoring the DVB-T2 multiplex used for HD services) use 64QAM and either 2/3 or 3/4 FEC and provide up to 24 Mbit/s. The difference in signal strength needed to receive a QPSK signal compared to a 64 QAM signal is around 11dB, meaning that if the local TV transmitter power is 11 dB (about a factor of 12 times) or so less than the main station, coverage parity is maintained. This was not the case for analogue broadcasts of local TV, and makes the case for local TV using DTT much improved. It still requires sensible transmitter powers from stations to provide coverage and not the 20dB or less that the original analogue local TV stations enjoyed (if enjoyed is the right word).

There are, however, two distinct problems with using main stations for local TV:

- The main stations are often well outside the areas where the audiences are located (you wouldn’t put a 300 metre tall mast in the middle of a housing estate). The strongest coverage area of such towers is therefore outside of the area where the audience is located thus exacerbating the lower power, lower height, out of group issues that the old analogue local TV stations faced. Fundamentally they don’t put the signal where it is needed if all you’re interested in doing is serving a local community. You almost never see local radio stations on the same masts as the main national services for exactly this reason. Even in London, local (capital wide!) services were transmitted on FM from Crystal Palace whereas the national services were transmitted from Wrotham which is around 20 miles south east of London in the county of Kent. Only in relatively recent years (compared to the age of the FM network) did the BBC add the national stations to the Crystal Palace site as (guess what...) the coverage of Wrotham in central London was not ideal.

- Secondly, the main station masts are expensive to use both because higher power transmitters are needed to reach the desired service areas, but also because the masts themselves are expensive to operate and maintain and this has to be passed on to any organisations using the sites. Similarly, given their relatively remote location, power, access and other services can be difficult to provide increasing the cost of using the site.

Although the coverage of the Fawley transmitter was not as widespread as that from Rowridge, in Southampton (the area of greatest economic interest) the Channel 5 analogue signal was good enough for most people to watch. Local TV channel Six TV also had a transmitter on the Fawley mast on channel 29 (also in-group) but with the slightly lower 4kW.

As with Six TV above, not all of the original analogue local TV stations used the main station masts.

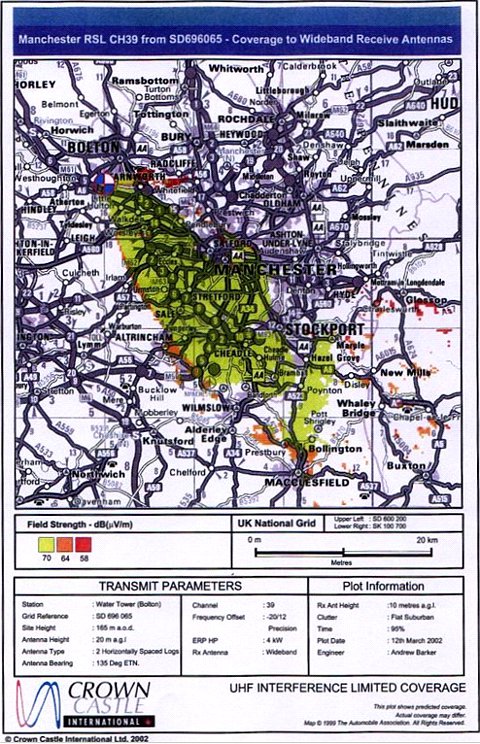

For example, Channel M in Manchester used a site on a water tower in Bolton. Like the Fawley solution for Southampton, this put the transmitter in roughly the right direction for viewers in Manchester whose antennas were pointed at the main station at Winter Hill. The frequency (channel 39) was, however, out of group and the transmitter pattern severely restricted to avoid interference with other transmitters and with the radioastronomy users at Jodrell Bank who used channel 38.

For example, Channel M in Manchester used a site on a water tower in Bolton. Like the Fawley solution for Southampton, this put the transmitter in roughly the right direction for viewers in Manchester whose antennas were pointed at the main station at Winter Hill. The frequency (channel 39) was, however, out of group and the transmitter pattern severely restricted to avoid interference with other transmitters and with the radioastronomy users at Jodrell Bank who used channel 38.  The upshot was that Channel M's signal was strong enough for good reception to a large number of viewers who were nearest to the water tower, but, conversely, coverage of Channel M in downtown Manchester was relatively poor (click on the map on the left to see it in full). Despite that, the station did better than many local TV companies and lasted for the best part of 12 years before finally closing down just before analogue services ended in the UK.

The upshot was that Channel M's signal was strong enough for good reception to a large number of viewers who were nearest to the water tower, but, conversely, coverage of Channel M in downtown Manchester was relatively poor (click on the map on the left to see it in full). Despite that, the station did better than many local TV companies and lasted for the best part of 12 years before finally closing down just before analogue services ended in the UK.What would have been great would to have been able to put more than one site on-air to provide additional coverage to fill-in coverage not-spots. In analogue terms this is difficult to do but for digital services such a solution is inherent to DTT in the form of a single frequency network (SFN). In an SFN multiple transmitters are put on the same frequency and as long as certain technical criteria are maintained (eg the distance between sites is small enough, ensuring that the transmitters are time and frequency synchronised, and that they carry the same content), they do not cause each other interference. In fact, the signals from multiple sites can even add together to improve coverage. If this sounds too good to be true, it is exactly how the digital audio broadcasting (DAB) multiplexes work.

So... Wouldn’t it be great if local TV in the digital age could take advantage of the use of SFNs to put a number of lower power (and thus much cheaper) transmitters right where their audiences are located, in line with existing masts (so that antennas don’t need re-pointing) and providing good coverage where the viewers are, but not wasting power or money on areas where few viewers are located? That is just the solution that Avanti’s bid to run the local TV multiplexes proposes. Whilst it might appear to be a ‘whacky, out-of-the-box’ type of solution, on the contrary it does what needs to be done in an efficient and effective way that has been proven to work well for local TV, even in the days of analogue transmission.

The jury (Ofcom) is still out on which of the bids to operate the multiplexes will succeed, but it is to be hoped that those making the decision are aware of the chequered history of local TV in the UK and don’t fall into the same traps that led to the commercial failure of the original analogue services in the 1990s and 2000s.

Tuesday 23 October, 2012, 07:48 - Licensed

Posted by Administrator

Have you ever read the book 'Freakonomics'? It tries to demonstrate that sometimes cause and effect are far, far removed from each other. Rather like Sherlock Holmes adage:Posted by Administrator

When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.

Take a look at the list of FM frequencies for radio stations in Dhaka, Bangladesh. It may not seem odd at first, but look closely:

88.0 MHz Radio Foorti

88.0 MHz Radio Foorti 88.4 MHz Radio Aamar

88.8 MHz Bangladesh Betar (Traffic Channel)

89.2 MHz ABC Radio

89.6 MHz Radio Today

90.0 MHz Capital FM

90.4 MHz Dhaka FM

90.4 MHz Dhaka FM91.6 MHz Peoples Radio

92.4 MHz Radio Shadhin

97.6 MHz Bangladesh Betar

100.0 MHz BBC World Service

103.2 MHz Bangladesh Betar (Home Service)

Taken from a variety of sources such as: Asiawaves

Notice anything odd? What about the fact that there are 7 stations spread out every 400 kHz between 88.0 and 90.4, two more below 93 MHz and then the rest of the whole FM band up to 108 MHz contains only 3 more stations.

The 400 kHz spacing is sensible (see the previous Wireless Waffle article on the bandwidth required to transmit a stereo FM programme), but why are they crammed down at the bottom end of the band? Here's a quick Wireless Waffle quiz. See if you can get the right answer.

Is it because:

- Propagation at lower frequencies is better than at higher frequencies and thus the lower end of the FM band will yield marginally better coverage than the top of the band for the same power/antenna.

- Like many countries (including the UK which only had access to 88.0 to 97.6 for a long time), the bottom of the band was opened up for broadcasting first, and the upper frequencies have only recently become available.

- Buildings in Dhaka are built to a Government controlled specification which, ironically, has a resonant frequency at the top of the FM band, causing signals at this end of the band not to be able to penetrate inside them.

- The majority of cars in Dhaka are imported from Japan which has an odd FM broadcasting band that runs from 76 to 90 MHz and thus the radios in those cars don't extend much above 90 MHz.

- The transmitters used by FM stations in Dhaka are very old and work best at the lowest possible frequency, giving the highest output power and greatest efficiency.

Well (a) is certainly true, though the difference in propagation is less than 20% between 88 and 108 MHz and is offset to some extent by the slightly better performance of receiving antennas at 108 compared to 88 MHz. As for (b), this is not true as the BBC service on 100 MHz has been on air for over 15 years and was one of the first FM stations in Dhaka. Answer (c) is a joke – have you seen the state of buildings in Dhaka?! Answer (d) could certainly be true as the Japanese FM band does run from 76 to 90 MHz. And finally (e) would be true of old transmitters were used, but most are modern and therefore don't suffer from this problem, which, as with (a) is pretty marginal anyhow.

Well (a) is certainly true, though the difference in propagation is less than 20% between 88 and 108 MHz and is offset to some extent by the slightly better performance of receiving antennas at 108 compared to 88 MHz. As for (b), this is not true as the BBC service on 100 MHz has been on air for over 15 years and was one of the first FM stations in Dhaka. Answer (c) is a joke – have you seen the state of buildings in Dhaka?! Answer (d) could certainly be true as the Japanese FM band does run from 76 to 90 MHz. And finally (e) would be true of old transmitters were used, but most are modern and therefore don't suffer from this problem, which, as with (a) is pretty marginal anyhow. The real reason that stations in Dhaka are clustered on frequencies around and below 90 MHz is (d). Think about it... when you listen to FM radio the most? Yes, perhaps you listen at home, especially on your alarm clock and in the morning, but most listening is done whilst in the car. There’s not much point being on a frequency that car radios can’t tune into and so there is the highest demand for frequencies on or below 90 MHz. Some older analogue radios will tune slightly above this so 90.4 MHz and thereabouts is not bad either. At the time of launch of the BBC service on 100 MHz there were very few cars (or FM radios for that matter) in Dhaka and so the issue didn't manifest itself.

The real reason that stations in Dhaka are clustered on frequencies around and below 90 MHz is (d). Think about it... when you listen to FM radio the most? Yes, perhaps you listen at home, especially on your alarm clock and in the morning, but most listening is done whilst in the car. There’s not much point being on a frequency that car radios can’t tune into and so there is the highest demand for frequencies on or below 90 MHz. Some older analogue radios will tune slightly above this so 90.4 MHz and thereabouts is not bad either. At the time of launch of the BBC service on 100 MHz there were very few cars (or FM radios for that matter) in Dhaka and so the issue didn't manifest itself.Did you guess right? Would you have guessed that the choice of FM frequencies was driven by car imports if it hadn't been suggested to you? We doubt it! A case of 'Freakonomics' that is perhaps best labelled 'Freakquencies'.