Friday 7 February, 2014, 13:43 - Broadcasting, Licensed, Much Ado About Nothing

Posted by Administrator

What a disappointment it was to find a recording called 90 years of the time pips, to discover that it is a special version of the pips¹ designed to celebrate their 90th birthday.Posted by Administrator

Wouldn't it have been more fun to have calculated how many pips there have been in 90 years and then created audio that just pipped (or beeped continuously) through all 90 years? How many pips would that be?

90 years × 365.25 days × 24 hours = 788,940 hours²

The first 5 pips have a duration of a tenth of a second, and the final pip has a duration of half a second, so the total duration of the pips each hour is exactly 1 second (5 × 0.1 + 0.5). A constant tone of duration 788,940 seconds (which is 9 days, 3 hours and 9 minutes precisely) would therefore represent '90 years of the time pips' much more accurately.

So here for your listening pleasure, is the Wireless Waffle tribute to the pips... 90 years of pips compressed into 9 days, 3 hours and 9 minutes.

¹ Not to be confused with Gladys Knight's backing group who, whilst also played on the BBC from time-to-time, are not the pips in question here.

¹ Not to be confused with Gladys Knight's backing group who, whilst also played on the BBC from time-to-time, are not the pips in question here.² Of course the pips have not been broadcast every hour over that period. Other time signals (such as the chimes of Big Ben) are used on some hours. Equally the BBC has not always been a 24 hour service, so this figure is probably a significant over-estimate.

add comment

( 585 views )

| permalink

|

( 3 / 2126 )

( 3 / 2126 )

( 3 / 2126 )

( 3 / 2126 )

Wednesday 29 January, 2014, 11:01 - Licensed

Posted by Administrator

It's a surprise that there haven't been more reports of this, but it seems that the Local TV services licensed by Ofcom last year are beginning to come online. The video clip below shows test of one of the two national channels that will be operated by Comux (to try and generate enough profit to run the transmitters) as received in Clacton, Essex. The signal comes from the Crystal Palace transmitter in London.Posted by Administrator

There doesn't yet seem to be placeholder for London Live which will launch in the capital in March on channel 8 on Freeview, but the two national channels awaiting launch and currently sat on channels 791 and 792 so you can check whether you will be able to receive it (a re-tune may be necessary).

The first of the new raft of local TV stations on the air was Estuary TV in Grimsby, whose transmitter also does a pretty good job of covering nearby Kingston-upon-Hull.

Wireless Waffle previously reported on the lessons to be learnt from the failed attempts at local TV in the UK in the past, and on the uncanny similarity between Comux (the local TV network operator) and Arqiva (who are providing the transmitters to Comux.

There are still a large number of local TV transmitters to be put on-air, so keep checking your set-top-boxes for new channels. Oh, and whilst you're at it, see if you can get the additional Freeview HD multiplexes that have quietly launched around the UK providing such excitement as BBC4 HD and Al Jazeera HD. Why couldn't they have put something useful in HD such as Dave or Film4?

You can check the channel line up on Freeview at your location by using the handy form below.

The BBC recently reported that Radio Russia have quietly switched off the majority of their long-wave broadcast transmitters. Whilst the silent passing of Russia's long wave service will not rattle the front pages either in Russia or anywhere else for that matter, it does raise the question of the long-term viability of long-wave broadcasting.

During the early 1990s there was a resurgence of interest in long-wave radio in the UK caused by the success of the pop station Atlantic 252. But by later in the decade, the poorer quality of long-wave broadcasting compared to FM, together with the increased proliferation of local FM services in the UK eventually led to the demise of the station. Similar logic appears to have been used by the Russian authorities who now have a much more extensive network of FM transmitters and clearly feel that the expense of operating long-wave is no longer justified.

During the early 1990s there was a resurgence of interest in long-wave radio in the UK caused by the success of the pop station Atlantic 252. But by later in the decade, the poorer quality of long-wave broadcasting compared to FM, together with the increased proliferation of local FM services in the UK eventually led to the demise of the station. Similar logic appears to have been used by the Russian authorities who now have a much more extensive network of FM transmitters and clearly feel that the expense of operating long-wave is no longer justified.

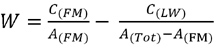

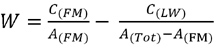

One of the great advantages of long-wave broadcasting is the large area that can be covered from a single transmitter. For countries whose population is spread over very wide areas, long-wave offers a means to broadcast to them with very few transmitters. Conversely, the large antennas and high transmitter powers required to deliver the service make it an expensive way to reach audiences. Presumably there is a relatively simple equation that describes the cost-benefit of long-wave broadcasting, i.e.:

Where:

As long as W>0 as A(FM) increases it continues to be worthwhile to broadcast on long-wave as the cost of providing the service is greater than the cost of doing the same thing using FM.

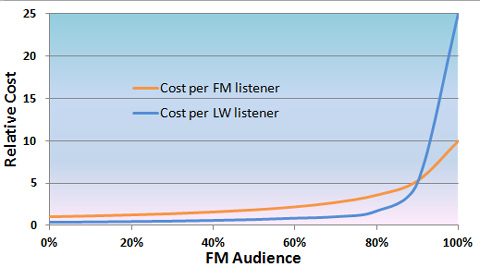

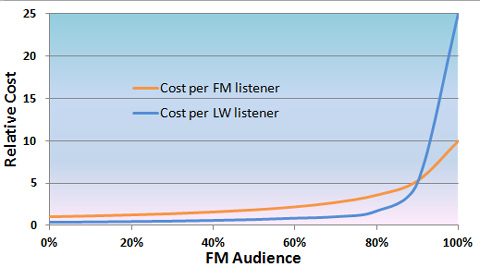

The cost of providing an FM service - C(FM) - is not constant, and will increase with the audience served, and not in a linear fashion either. The final few audience will cost significantly more than the first few. This is because stations which only serve small, sparse communities tend to be more costly (per person) than ones serving densely packed areas.

The cost of providing the LW service - C(LW) - however, is largely constant regardless of how many people listen to it.

It's therefore possible to draw a graph of the cost per person - C/A - of the FM audience and the cost per person of the long-wave audience, as the FM audience increases.

The figures used in the graph above are illustrative only. They assume that:

Of course there are many other factors to take into account, in particular the difference in service quality between FM and long-wave, and the proportion of receivers that have a long-wave function. There are thus other factors that will hasten the end of long-wave as FM coverage increases. The same could largely be said for medium-wave where arguably, the problems of night time interference make it even worse off than long-wave (though more receivers have it).

Wireless Waffle reported back in 2006 on the various organisations planning to launch long-wave services, not surprisingly none of them have (yet) come to fruition.

Wireless Waffle reported back in 2006 on the various organisations planning to launch long-wave services, not surprisingly none of them have (yet) come to fruition.

There is, however, one factor in favour of any country maintaining a long-wave service (or even medium-wave for that matter), and it's this: simplicity. It is possible to build a receiver for long-wave (or medium-wave) AM transmissions using nothing more than wire and coal (and a pair of headphones) as was created by prisoners of war.

In the event (God forbid) of a national emergency that took electricity (such as a massive solar flare), it would still be possible for governments to communicate with their citizens using simple broadcasting techniques and for citizens to receive them using simple equipment. Not so with digital broadcasting! Ironically, most long-wave transmitters use valves which are much less prone to damage from solar flares than transistors.

So whilst long-wave services are on the way out in Russia and elsewhere, it will be interesting to see whether the transmitting equipment is completely dismantled at all sites, or whether some remain for times of emergency. Of course if every long-wave transmitter is eventually turned off, there is some interesting radio spectrum available that could be re-used for something else... offers on a postcard!

During the early 1990s there was a resurgence of interest in long-wave radio in the UK caused by the success of the pop station Atlantic 252. But by later in the decade, the poorer quality of long-wave broadcasting compared to FM, together with the increased proliferation of local FM services in the UK eventually led to the demise of the station. Similar logic appears to have been used by the Russian authorities who now have a much more extensive network of FM transmitters and clearly feel that the expense of operating long-wave is no longer justified.

During the early 1990s there was a resurgence of interest in long-wave radio in the UK caused by the success of the pop station Atlantic 252. But by later in the decade, the poorer quality of long-wave broadcasting compared to FM, together with the increased proliferation of local FM services in the UK eventually led to the demise of the station. Similar logic appears to have been used by the Russian authorities who now have a much more extensive network of FM transmitters and clearly feel that the expense of operating long-wave is no longer justified.One of the great advantages of long-wave broadcasting is the large area that can be covered from a single transmitter. For countries whose population is spread over very wide areas, long-wave offers a means to broadcast to them with very few transmitters. Conversely, the large antennas and high transmitter powers required to deliver the service make it an expensive way to reach audiences. Presumably there is a relatively simple equation that describes the cost-benefit of long-wave broadcasting, i.e.:

Where:

W = Worthwhileness of Long-Wave Broadcasting

C = Total cost of providing the service

A = Audience

FM = FM

LW = Long Wave

Tot = Total

C = Total cost of providing the service

A = Audience

FM = FM

LW = Long Wave

Tot = Total

As long as W>0 as A(FM) increases it continues to be worthwhile to broadcast on long-wave as the cost of providing the service is greater than the cost of doing the same thing using FM.

The cost of providing an FM service - C(FM) - is not constant, and will increase with the audience served, and not in a linear fashion either. The final few audience will cost significantly more than the first few. This is because stations which only serve small, sparse communities tend to be more costly (per person) than ones serving densely packed areas.

The cost of providing the LW service - C(LW) - however, is largely constant regardless of how many people listen to it.

It's therefore possible to draw a graph of the cost per person - C/A - of the FM audience and the cost per person of the long-wave audience, as the FM audience increases.

The figures used in the graph above are illustrative only. They assume that:

- The cost per person of providing an FM service increases by a factor of 10 between the first and the last person served;

- The cost per person of providing the long-wave service is initially only a third of that of providing the same service on FM.

Of course there are many other factors to take into account, in particular the difference in service quality between FM and long-wave, and the proportion of receivers that have a long-wave function. There are thus other factors that will hasten the end of long-wave as FM coverage increases. The same could largely be said for medium-wave where arguably, the problems of night time interference make it even worse off than long-wave (though more receivers have it).

Wireless Waffle reported back in 2006 on the various organisations planning to launch long-wave services, not surprisingly none of them have (yet) come to fruition.

Wireless Waffle reported back in 2006 on the various organisations planning to launch long-wave services, not surprisingly none of them have (yet) come to fruition. There is, however, one factor in favour of any country maintaining a long-wave service (or even medium-wave for that matter), and it's this: simplicity. It is possible to build a receiver for long-wave (or medium-wave) AM transmissions using nothing more than wire and coal (and a pair of headphones) as was created by prisoners of war.

Prisoners of war during WWII had to improvise from whatever bits of junk they could scrounge in order to build a radio. One type of detector used a small piece of coke, which was a derivative of coal often used in heating stoves, about the size of a pea.

After much adjusting of the point of contact on the coke and the tension of the wire, some strong stations would have been received.

If the POW was lucky enough to scrounge a variable capacitor, the set could possibly receive more frequencies.

Source: www.bizzarelabs.com

In the event (God forbid) of a national emergency that took electricity (such as a massive solar flare), it would still be possible for governments to communicate with their citizens using simple broadcasting techniques and for citizens to receive them using simple equipment. Not so with digital broadcasting! Ironically, most long-wave transmitters use valves which are much less prone to damage from solar flares than transistors.

So whilst long-wave services are on the way out in Russia and elsewhere, it will be interesting to see whether the transmitting equipment is completely dismantled at all sites, or whether some remain for times of emergency. Of course if every long-wave transmitter is eventually turned off, there is some interesting radio spectrum available that could be re-used for something else... offers on a postcard!

Thursday 4 April, 2013, 22:05 - Licensed, Spectrum Management, Chart Predictions

Posted by Administrator

Posted by Administrator

It is now only a month or so before the annual pan-European musical bun fight that is the Eurovision Song Contest (which is on the 18th of May). The 39 songs that have made it to the competition (which this year is in Malmo, Sweden) are now available to listen to online - with many having professionally produced videos viewable on YouTube. As always there is a mix of complete Euro-nonsense (Greece with their song Alcohol Is Free), songs that could have been written for Eurovision any time from 1960 to the present day (Switzerland's song You And Me falls into this category) copies of last year's winner in the hope that people will want the same thing again this year (Germany's Glorious for example), sickly pop songs with no real substance (Finland's Abbaesque entry Marry Me) and this year, it seems, a whole swathe of rather nice ballads.

It is now only a month or so before the annual pan-European musical bun fight that is the Eurovision Song Contest (which is on the 18th of May). The 39 songs that have made it to the competition (which this year is in Malmo, Sweden) are now available to listen to online - with many having professionally produced videos viewable on YouTube. As always there is a mix of complete Euro-nonsense (Greece with their song Alcohol Is Free), songs that could have been written for Eurovision any time from 1960 to the present day (Switzerland's song You And Me falls into this category) copies of last year's winner in the hope that people will want the same thing again this year (Germany's Glorious for example), sickly pop songs with no real substance (Finland's Abbaesque entry Marry Me) and this year, it seems, a whole swathe of rather nice ballads. For what it's worth, Wireless Waffle is particularly fond of the Icelandic entry (Ég á Líf), the video for which awaits your enjoyment below. If you are of an emotionally sensitive disposition, make sure you have some tissues to hand.

Our selection of songs that ought to be in the top 5, at least if they are able to reproduce the performance in their videos on stage on the night are:

- Eyþór Ingi Gunnlaugsson - Ég á Líf (Iceland)

- Roberto Bellarosa - Love Kills (Belgium)

- Zlata Ognevich - Gravity (Ukraine)

- Despina Olympiou - An Me Thimáse (Cyprus)

- Dina Garipova - What If (Russia)

What has become more complex, though, is the use of wireless technology for the event. Whilst it's still normal in a concert hall to use wired cameras, the use of radiomicrophones and in-ear monitors (which allow the performer to hear themselves sing without the noise of the surrounding environment) has grown significantly over recent years. Figures provided in response to a European Commission consultation on programme making spectrum show an average annual growth of 12% in the number of such devices employed over the past 15 years (but nearly 40% growth per year over the last 4 years).

| Year | Venue | Radiomicrophones used | In-Ear Monitors used |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | Birmingham, UK | 40 | 2 |

| 1999 | Jerusalem, Israel | 42 | 6 |

| 2000 | Stockholm, Sweden | 48 | 16 |

| 2001 | Copenhagen, Denmark | 48 | 16 |

| 2002 | Tallinn, Estonia | 54 | 16 |

| 2003 | Riga, Latvia | 54 | 16 |

| 2004 | Istanbul, Turkey | 54 | 16 |

| 2005 | Kiev, Ukraine | 54 | 16 |

| 2006 | Athens, Greece | 54 | 16 |

| 2007 | Helsinki, Finland | 56 | 16 |

| 2008 | Belgrade, Serbia | 56 | 16 |

| 2009 | Moscow, Russia | 56 | 16 |

| 2010 | Oslo, Norway | 72 | 32 |

| 2011 | Düsseldorf, Germany | 82 | 40 |

| 2012 | Baku, Azerbaijan | 104 | 80 |

What is driving this growth? One the one hand, the equipment costs are coming down making it more affordable to use wireless microphones. On the other, it's also probably true that in earlier years, microphones would be passed from one user to another as they went on/off stage whereas now each artist and band has their own set of equipment which is tailored to their own needs.

Equipment is one thing, but what about the radio spectrum issues? Radiomicrophones and in-ear monitors are normally analogue (for reasons that can wait for another day) and use around 200 kHz of spectrum each. If all the devices in Baku (184) were turned on at the same time, they would need 37 MHz of spectrum just to exist. But this is not the full story. Firstly, if devices were 200 kHz apart, there would be not a sliver of a gap between them. Whilst they could all successfully transmit, even the smartest digital receivers would find it difficult to separate them from each other - and we aren't dealing with digital technology. In reality, frequencies are separated by at least 300 kHz and often more to allow the receivers room to breathe.

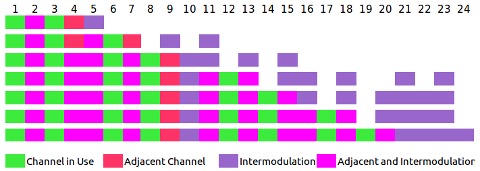

The situation is even worse than this however. Due to the close proximity of devices to each other, and of devices to receivers, there is a tendency for lots of intermodulation to occur. If you assume that each 200 kHz channel that can be used is numbered, starting at 1 then you can't use the adjacent channel because it's too close. You also, because of intermodulation, can't use any channel which represents the difference or sum of twice the value of one channel being used minus another channel being used. As and example:

- If you are using channels 1 and 3 (channel 2 is adjacent to channel 1, so you can't use that), you can't use channel 4 (as its adjacent to 3) or channel 5 (as its 2*3-1). The next available channel is 6.

- If you are using channels 1, 3 and 6, you now also can't use channel 7 (adj to 6). The next available channel is 8.

- If you are using channels 1, 3, 6 and 8 you now can't use channels 9 (adj to 8), 10 (2*8-6) or 11 (2*6-1). The next available channel is 12.

The diagram below shows the situation. Green channels are those in use. Red channels are adjacent channels that can't be used. Purple channels are intermodulation products. Pink channels are both at the same time!

In the example given above, out of 24 available channels, only 8 are useable. Actually, if you extended the diagram at this point you would find that another 10 channels are already 'wallied out' because of intermodulation. So 8 transmitters has used 34 frequencies! The relationship between the number of transmitters on-air and the number of channels sterilised is not linear but in general something of the order of 1 frequency in 5 can be used for radiomicrophones where they are packed densely in a given location if these problems are to be avoided.

This represents pretty poor frequency efficiency but is fairly representative of what is achieved in real life, which is that only something like one fifth of any spectrum available for radiomicrophones or in-ear monitors can be used in any one venue at the same time. Returning to Baku then, the amount of spectrum required is not 37 MHz, but to support 184 devices simultaneously would require more like 184 MHz of spectrum: give or take 1 MHz per device!

Most radiomicrophones (and in-ear monitors) operate in and amongst television broadcasts in the UHF band which notionally runs from 470 to 862 MHz. In many countries, however, the upper end of this band from 790 MHz upwards has now been set-aside for mobile broadband services, leaving 320 MHz remaining for television broadcasting (and of course radio microphones).

Azerbaijan, last year's host of the Eurovision, is yet to switch over to digital TV and equally has not yet used the upper part of the UHF TV band for mobile services and so finding 180 MHz of spectrum for radiomicrophones is presumably not that difficult. In 2013, however, the contest is in Malmo, Sweden. Not only has Sweden cleared the upper part of the UHF band for mobile services, but it has also gone over to digital broadcasting. Malmo is virtually on the border between Sweden and Denmark meaning that the local TV spectrum will be occupied not only by the 8 Swedish multiplexes but by the Danish ones too. Finding 180 MHz of spectrum for this year's competition is therefore much more challenging.

Azerbaijan, last year's host of the Eurovision, is yet to switch over to digital TV and equally has not yet used the upper part of the UHF TV band for mobile services and so finding 180 MHz of spectrum for radiomicrophones is presumably not that difficult. In 2013, however, the contest is in Malmo, Sweden. Not only has Sweden cleared the upper part of the UHF band for mobile services, but it has also gone over to digital broadcasting. Malmo is virtually on the border between Sweden and Denmark meaning that the local TV spectrum will be occupied not only by the 8 Swedish multiplexes but by the Danish ones too. Finding 180 MHz of spectrum for this year's competition is therefore much more challenging.But move forward 10 years and then what will happen. For starters, at the current rate of growth, and assuming no improvement in the spectrum efficiency of wireless microphone technology, there will be a requirement for 560 MHz of spectrum for the Eurovision. Secondly, the parts of the UHF TV band currently unoccupied and used for these purposes will be full of 'cognitive radio' devices hunting out every last vestige of unused spectrum. What will happen then? The simple fact is that no-one really knows, but the programme making community are worried, and understandably so. If there was a way around the intermodulation problem, then the amount of spectrum required would decrease, so perhaps now is the time for some enterprising RF engineer to find a solution to this problem so that we can continue to enjoy the pageantry of the world's greatest song contest. Either that or sing less? Some would argue that for the Eurovision that would be no bad thing.